Today’s episode of Research Like a Pro is about records created during the New Deal in the 1930s that can help research African American ancestors. This is the third part in our series on researching African Americans in federal government documents. Diana shares more record groups she learned about during her IGHR course, including the 1940 census, WPA Personnel records, CCC Enrollee Records, the American Guide Series, Slave Narratives, and the Historical Records Survey.

Transcript

Nicole (0s):

This is Research Like a Pro episode 123 African American Research Part Three. Welcome to Research Like a Pro a Genealogy Podcast about taking your research to the next level, hosted by Nicole Dyer and Diana Elder accredited genealogy professional. Diana and Nicole are the mother-daughter team at FamilyLocket.com and the creators of the Amazon bestselling book, The Research Like a Pro a Genealogists Guide. I’m Nicole co-host of the podcast join Diana and me as we discuss how to stay organized, make progress in our research and solve difficult cases. Let’s go, Hi Everyone.

Nicole (44s):

And welcome to Research Like a Pro, I’m Nicole Dyer, and I’m here with my mom accredited genealogist, Diana Elder. Hello mom. How are you?

Diana (53s):

I’m doing well. Having recovered from Halloween weekend and excited to get back into my genealogy and talking today on the podcast about some fun things.

Nicole (1m 6s):

Yeah, me too. We sure had a fun time Halloween dressing up. And my daughter was a light-up butterfly with the big glowing wings. So that was very entertaining.

Diana (1m 18s):

I bet she loved that. That’s so fun.

Nicole (1m 20s):

So today is our third episode where we’re going to talk about researching African-American ancestors in government documents. So what record types are we going to focus on today?

Diana (1m 31s):

Today we’re talking all about WPA Projects and Slave Narratives, and these are amazing. I have had so much fun learning about them and seeing the information that’s available online to lead you, to finding these records for your ancestors. And so I think it will be really beneficial and whether you have African-American ancestors or you’re researching someone with African-American ancestry or not, your ancestor could be in this because the WPA and the New Deal obviously was nationwide. So there’s a lot of value for every researcher in these records.

Nicole (2m 10s):

Yes, I’ve used some of the documents created by the WPA at this time period in the 1930s and the cemetery transcriptions. And some of the other record inventories that they did are really useful.

Diana (2m 24s):

Yeah. And I didn’t even know that these existed until I started preparing for accreditation and I was doing my locality guides for each state, and I kept coming across these WPA Projects where they would go into a county and inventory all of the records, or all of the churches. It’s amazing. And you can find these on FamilySearch, you can do a locality or a place search, and then look at WPA, maybe put it in the keyword and find some of these inventories. So that’s something that I’d use before, but in our course, the course Researching African American Ancestors: Government Docs and Advanced Tools, we spent at least two sessions talking about the records from the New Deal.

Diana (3m 12s):

And so that’s what we’re going to focus on today. And specifically with thinking of how African-Americans were listed in these records and what information we can discover for them.

Nicole (3m 23s):

So start with the New Deal.. What was the New Deal.and how did it impact the lives of Americans and African-Americans during the thirties?

Diana (3m 33s):

Well, if we step back in time, we have President Roosevelt who had just been elected in 1933, and this was the Depression era. And one out of five Americans had no work. And in the African-American population, the percentage of unemployed was even higher. So FDR initiated a variety of projects and he called them the New Deal. Now, one of the really neat websites that I discovered from my class was a website called The Living New Deal. And it is one of those websites that you can stay on for a long time, because it has a really great interactive map.

Diana (4m 18s):

So you have this map and it reports 16,419 sites throughout the United States that had something to do with the New Deal, was a project, and every little dot there’s red dots and you can zoom in on them. And every dot is a New Deal site. So you zoom in on a place that you think your ancestor might’ve lived and you can see projects, and then envision in that town where your ancestor lived. He could have been a worker on that site. And so there are local landmarks, there’s buildings, so many different things that were constructed through new deal projects.

Diana (4m 60s):

So of course, what do you do when you go to a new site? You know, I always just go to my hometown cause I’m really curious. Was there anything in my hometown of Burley, Idaho, and there was right there on the map, it explained that the post office in Burley, that I went to all the time growing up, was constructed by the Treasury Department with their funds in 1935. And it has an example of New Deal artwork and it is still in service, which I can attest to. So that was really fun, that kind of hit home. And so they would come in and with funding from the government, they would hire local workers to work on these projects.

Diana (5m 43s):

Some of the things that I thought they built were a lot of post offices, but also libraries, court houses, roads. I mean, there’s so many different things that were built and they employed the local people who needed a job.

Nicole (5m 57s):

Oh, great. Well, I was playing with the website too and looking in Tucson to see what the New Deal sites are here. And one of the places that we have visited before as a tourist site, Colossal Cave Park was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps. So that’s kind of neat to see different sites around here. It seems like they did a lot of road building and recreational park type places as well.

Diana (6m 22s):

They did, and they broke it down into a lot of different categories. And so when you go to the website, The Living New Deal, you can use the map to hone in on different locations, or you can just go to the different agencies and then you’ll be blown away by how many different agencies there are and then how many different projects there are. So it’s a really fun website to take a look at and get an idea of how all this came together. It was huge. This was a huge project and it created records because the government kept records and it might really have some good clues for your ancestor.

Diana (7m 2s):

So under this overarching New Deal, one of the big programs that we already talked about was the WPA, the Works Progress Administration. And this is the one that they would go in and build bridges, dams, roads, housing projects, and public buildings. So this was a unique partnership between the local, the federal and the state governments, the local city and county governments had to propose the projects and then the federal government would approve them. And then they could hire the local unemployed individuals to do the work and the federal government paid the wages.

Diana (7m 42s):

So if you were in a little community like Burley, Idaho, and you said, we need a post office, let’s see if we can get some funding, you would create a plan and send that in and try to get that approved so that you could get funding to build your post office. So you can imagine when the word got out that all these local governments were proposing a lot of projects. So like you were saying in Tucson, there’s a lot of neat things that were created at this time because of this whole program.

Nicole (8m 14s):

So what can we do, you know, to kind of learn if our ancestor was involved in the WPA?

Diana (8m 21s):

Well, that’s kind of one of the tricky things. One of the things we can think about is what our ancestors were doing. You know, sometimes there’s family stories that come down that they worked on a project, or we know that maybe they had construction skills or, you know, something that could have been used in one of these projects. So if we’re thinking about African-Americans, let’s, let’s go a little specific here. There is a good chance that an African-American ancestor was employed by the WPA because the unemployment rate was so high and many of the African-Americans were employed for construction projects because they hadn’t been given opportunities for some of the more skilled jobs, but there were also opportunities for white collar jobs, but this was an era of discrimination.

Diana (9m 17s):

And so there weren’t as many opportunities for the African-Americans as their white counterparts in those skilled white collar type jobs. So you’re probably going to find your African-American ancestors more in the construction projects. So a good clue to whether your ancestor was involved is starting with a home sources. So maybe there’s photographs of an ancestor working on a project. There were membership cards issued, and these could have been saved as momentoes. But one of the things that we’ll probably want to use and is widely available for anyone researching is the 1940 census, and that had so many questions on it.

Diana (10m 4s):

And this is one that might have been ignored by us because we didn’t even think about these types of records. So the 1940 census asked specific questions about employment during the week of March 24th through March 30th in 1940. And if an ancestor had worked on a WPA Project before or after that week, they would not be listed. But if they were working on a WPA project right during that week, then they would have yes on it. So it’s kind of narrow, but it is a clue.

Nicole (10m 35s):

Oh, interesting. That’s fun that the 1940 census has that question on it. Something I didn’t know. And you’re right. Probably a lot of us have ignored that column, but what a good time to go and check and look and see if our ancestor worked for the WPA Projects that week? How funny that, you know, it was only during that one week.

Diana (10m 54s):

It is funny. And what I did was I just went to a location I was researching and I scanned the census to see if anybody had said yes, because I was just curious, was there anything going on in this location at that time? And it was fun to see some of the different people that did have Yes. And so it, line 21 asked the question, was this person at work for pay or profit in private or non-emergency government work during the week of March 24th through 30th. And so they were just to put yes or no there, and then line 22 says, if not, was he at work on or assigned to public emergency work, the WPA, NYA, CCC, et cetera, during that week.

Diana (11m 40s):

So you might have those initials, WPA, NYA, CCC in that column. And then that will let you know that there could be a record for your ancestor because he was actually working on one of those. So it’s fun to go look at. I mean, there’s a probability that they worked on a project and are not listed there in the 1940 census because it was before or after that date. But that is a good starting point. And it’s good to look at the specific projects in the area and think about whether they may have worked on them.

Nicole (12m 15s):

Hmm. That’s so interesting.

Diana (12m 17s):

So the NYA we haven’t talked about, and that’s one of the ones that could be listed there on that 1940 census. So NYA stands for National Youth Administration, and this was the program designed for the youth. It was ages 16 to 25 and it was part of the WPA. So we have this overarching umbrella of the WPA and then different things within it. And this was administered on the local level. And the whole idea of this program was to teach the young people skills and they were occupational skills. So they were setting up programs for anything from construction to nursing.

Diana (12m 59s):

And so you can search for the information about the NYA in the state. I had ancestors in Oklahoma at this time, and I found on the Oklahoma historical society and really great article talking all about the National Youth Administration in Oklahoma. And it talks all about the program, how they administered it. And it has a lot of information on the African-American NYA participants. So I thought that was really interesting on this state historical society page that they included so much. So maybe a good strategy would be to Google the state and NYA and see if you can find any information out there.

Diana (13m 41s):

If you had ancestors that were in that age grouping of 16 to 25, and maybe they could have been involved.

Nicole (13m 48s):

Oh, good idea. So if you do find out that they were involved, is there some kind of record group somewhere that we can look at that tells us more about them?

Diana (13m 58s):

Right. So all of these WPA personnel records are held at the National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri. And there’s a form that you fill out and you have to have as much information as you can about them. So you’re going to want to have done some really good research to get all these facts nailed down before you fill out the form and an order of the search. So you’re going to want a name, complete name as possible birth date, social security number, birth place, the hometown at the time of employment, parents’ names and spouses names. So those are all the categories on the form. It’s NARA form 14137, and it’s called the Requests Pertaining to WPA Personnel records.

Diana (14m 43s):

So whenever I do something like these searches, I like to do a lot of research before I send in that form, trying to get as correct of information as possible. And then you can submit your form and who knows what you’re going to get back. You know, it’s like any of these government records, you might get just like a simple one page, informational paper on them, or you could get a whole file. We just never know. It’s always an adventure.

Nicole (15m 11s):

Yeah, it is always an adventure. And it’s part of the reasonably exhaustive research that we do when we learn about a record that we could use to learn more about.

Diana (15m 22s):

Right. And sometimes we think that there may not be genealogical information in some of these records, but you never know, you know, especially with African American Research, we’re always trying to build up the FAN club and trying to find connections in the community and family members. And so every single record that we can track down can be a clue to that. So when we’re doing this hard research, we really do need to do reasonably exhaustive research and try to find all the records.

Nicole (15m 53s):

Yes. All right. Let’s talk more about some of these other programs in the New Deal. What else was there?

Diana (15m 59s):

Okay. One of the other little acronyms on the 1940 census was CCC, which stands for Civilian Conservation Corps. And this was the largest employer of young African-American men under the New Deal era. To be eligible, you had to be single between the ages of 17 and 28 years. And these young men were put to work on a lot of conservation projects like soil erosion projects, timbering improving recreational facilities and constructing roads. So like the one that you found in Tucson that was some by the CCC, right?

Nicole (16m 40s):

Yes.

Diana (16m 40s):

So these young men, they had work camps that they would live in and they would set up a camp and moved to this area and then do this project. And if you have an African-American ancestor who was between those ages of 17 to 28 years during the 1930s, really worthwhile to look into whether he could have been employed and think of the high unemployment rate with African-Americans and here’s an opportunity to go and work and earn some money. So it could be that the ancestor is not working in an area near his hometown, but could have gone out to one of these outlying areas.

Diana (17m 21s):

So you have to keep an open mind and think, well, okay, he might have been living in Texas, but then this project opened up in Arizona and went out there to be part of it. So what you can do is just do as much research as you can, to try to figure out if an ancestor could have been there. You will want to, again, apply through the National Archives at St. Louis and you still need all that good information that we talked about before. So if you get their service record, here are some of the things that might have, it might have the closest relative, their address, the date of their enrollment, their salary, their education, physical characteristics, date, and locations of service and campus assignment numbers.

Diana (18m 8s):

That would be really fun to get one of those records. And I’m trying to think if I have any ancestors that might’ve been the right age, but I think none of my main line ancestors were quite the right age. They were all too old or too young for that specific program.

Nicole (18m 24s):

That would be fun to get that record though, to learn about their education, their physical characteristics. It sounds a lot like what you might find on a military service record as well with the closest living relative and the date of enrollment and those kinds of

Diana (18m 38s):

Things. Yeah, it does.

Nicole (18m 39s):

And those are always nice because they give an exact birth date.

Diana (18m 43s):

Right. And the government records that have exact birth dates are generally a little bit more reliable because it’s generally the individual giving that information. Right.

Nicole (18m 53s):

Unless they had a reason to give a different year or something.

Diana (18m 58s):

Yeah. And it could be with these types of records since they did have that specific time frame that someone could have fudged on their birth year. So they would appear older or younger so they could work. So that’s always something to keep in mind, is there a motivation to change the birth year?

Nicole (19m 15s):

Right. So let’s talk now about some of the different writing projects, the narratives that were created during this time period and what we can learn about our African-American ancestors from them.

Diana (19m 27s):

All right. There’s the Federal Writers’ Project, which honestly I did not know much about until I took the course of the summer and it turns out it was one of the most significant of the New Deal projects and a great use for us as genealogists. So think back again to the 1930s and this huge unemployment rate. Well, among the unemployed, were those in the category of writers, teachers, librarians, historians, and others who worked with the written word. So there was a need to put this group of people to work. And so we have some really neat projects that were created because of the federal writers’ project.

Diana (20m 10s):

So the first one that we’re going to talk about is the American Guide Series. And this was new to me. This is an exciting thing to talk about because this is something that is becoming digitized and available more online. So what is the American Guide Series? This was created to stimulate travel and the economy. So remember this is the depression, the government’s trying to get people out of their houses, go travel, go spend money in these local communities. So it was to try to get people to get out of their home towns. They’ve these were a comprehensive guides to the scenic historical archeological, cultural and economic resources of the United States.

Diana (20m 54s):

So instead of going to Google and putting in some state and seeing what you can go look at, you know, what national parks are there, or what interesting scenic drives there could be. They put together these pamphlets and they cover whole regions and territory. They might cover just the city, might be just the state. There’s just a whole variety of them. And the best place to start searching for those is on Wikipedia. There’s a page called the American Guide Series and it has the table it’s organized by location. And it has a link to the digitize book or pamphlet on a variety of our favorite websites like Google books, Hathi Trust or Internet Archive.

Diana (21m 36s):

So it’s really fun to explore that and see what you can find. If you’ve been wanting to know what people thought about your local hometown or an area you’re researching in the 1930s, what a fun place to see the description of it at that time and period.

Nicole (21m 51s):

Well, that’s interesting. So how can this help us with African American Research?

Diana (21m 56s):

Well, if you are trying to learn more about place and time, we’re always needing to put our ancestors in the context of where they were living. So we can look at those guides and try to see what was there in their area. What could their life have been like? Was there something that drew people to their town? Was there something that they would have gone to visit? I know in my personal holdings, I’ve got a picture of my Shults family clan at Yosemite in California. And it’s so fun to see this huge group of people there amongst these great big trees.

Diana (22m 36s):

So it just gives you maybe a little bit more idea of what could be happening in their lives.

Nicole (22m 41s):

Yeah, that’s great. It’s always important to learn about the history of an area, any of the narratives that people in the town shared, possibly, maybe studies of the ethnic groups in the area could be useful. Anything that they might’ve included. It’ll be interesting to study these more

Diana (22m 59s):

And it was fun because they are more available. Now these are becoming digitized and put out on the, those major websites.

Nicole (23m 7s):

Yeah, it’s great. Anytime there’s a kind of a movement for writing history it always is exciting to us, historians and genealogists. So it’s great that there was that 1890s time when they wrote all the county histories and then another wonderful time in history, this 1940s federal writers’ project, where they’re researching these towns and writing about them.

Diana (23m 29s):

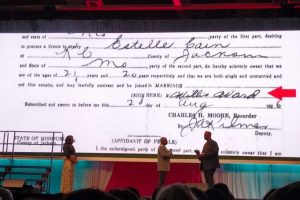

Yeah, it’s really great. One of the projects that those of you listening might have heard about, especially if you’re researching African-Americans is the Slave Narratives Project, and this is probably the best known of the group. If you’re an African-American researcher, arguably most valuable. This contains 2300 accounts of slavery told by formerly enslaved people who were still living at the time. And these narratives organized by location and then by surname. Often they have photographs and this is a compelling collection. So you need to know that the Library of Congress hosts a large collection of these records, but it’s not all inclusive.

Diana (24m 16s):

So for instance, the African-American Experience in Ohio is a web page. That’s available only on the Ohio History Connection website, and it has 27 interviews. So just like any record, we have to be careful of thinking they’re all in one place. So if you have looked at this briefly, didn’t find your surname or your ancestor, and then thought, okay, there’s no value for me. Remember that we need to use the FAN club principle. Your ancestor may not be listed there, but look for friends, neighbors, or associates that might have been part of your ancestor’s life, learning, their stories can shed light on your ancestor.

Nicole (24m 60s):

Slave Narratives are just wonderful. That’s so neat that those are available.

Diana (25m 4s):

Yeah. And one of the examples that I looked at was an interview with a gentleman who was born into slavery in 1861. And he described the slave owner, the home and his father’s experience in the civil war and life after the war. And at the very end, there is the note where they’re describing him. So whoever was taking down his narrative wrote this description that William P Hogue, 76, tall, still straight, slender build and wears a mustache and beard, iron gray like his hair. So how neat that you get a description and not to mention that you get their perspective several years later.

Diana (25m 47s):

So this gentleman was 76 and he has firsthand account of what it was like. He may not have remembered, or maybe he did, as the young child being enslaved, but he certainly would have known everything about emancipation and I’m sure lots and lots of stories from his parents and fathers. So really worthwhile to seek out those records and see what you can learn.

Nicole (26m 14s):

Yes. I think these have been a valuable resource for historians and can also be useful for genealogists as well, just a peek into this time period of American history and understanding what happened as far as we can from these memories that were recorded.

Diana (26m 30s):

Right? So to finish up our discussion on these records of the WPA, we have the historical record survey, which were what we had experienced with as genealogists. And this, what we talked about at the beginning of the podcast, and this is such a fun collection to look at. This was a project that sent workers into local archives. So they really did surveys of so many things. They did federal archives surveys of county records, church records, manuscripts, a huge variety of records here. So for example, if you are interested in knowing about African-American churches that were in the area where your ancestors lived in the 1930s, and before this inventory could give you a huge list of churches that you would want to research.

Diana (27m 24s):

So how can you find this well, search the FamilySearch catalog by the keyword ‘historical record survey’, and then the location that you’re interested in, and then you can see what inventories are available. And from my experience, most of these have been digitized and are available online. If they are not, you could also try searching on Hathi Trust, Google books, Internet Archive, some of our other websites that digitize books really worthwhile to take a look in your area and see what historical records survey projects were done there. Good idea. So just searching in the FamilySearch catalog I found as part of the Michigan historical records survey project, a calendar of the John C Dancy correspondence, 1898 to 1910, and this was an African-American individual and it has got 37 pages that you can view online.

Diana (28m 26s):

It’s a calendar of his correspondence, so it’s not the entire collection, but it tells you what’s in that collection that you could then find the actual records. So you never know what you’re going to find. It’s always an adventure. And it’s fun to just get started exploring some of these record groups that you may not have been aware of that were created during the 1930s and forties as part of the new deal.

Nicole (28m 53s):

It is wonderful now how so many websites have digitized some of these older books from the historical record survey and just making them much more available from what I understand, some of the actual records that were surveyed aren’t even available anymore, but it can be helpful to know that they did exist sometimes. And we can possibly use that as evidence of record loss if we need to.

Diana (29m 15s):

Oh, that’s a great point. And I think it’s really valuable specifically for church records and churches, because those are some of the record types that we really want. And then we find out there was just nothing left and I’ve had that happen in Oklahoma where I’ve been researching my ancestors and I know they attended church cause they have that in their, their histories. And when I contacted the local area, they’ll say, oh yeah, there’s no records anywhere. And you never know if that’s really true or not. But looking at that historical records project in the area and seeing that, oh wow, there were 15 churches that were there at that time. That can be really helpful just to know that your ancestor could have gone to any one of those.

Diana (29m 58s):

And maybe if you continue your research, you can actually find some records.

Nicole (30m 3s):

Yeah, that’s true. Just knowing what existed can give you a leg up because then you’ll have a name to search for when you look in different archival and manuscript collections. Right.

Diana (30m 13s):

Well, that was really fun. Yeah. This is one of my favorite takeaways from my course, this whole discussion on the New Deal and the record’s created. Really interesting to think about where our ancestors were. And if you have African-American ancestors, you know, really thinking about how they could have been employed during this era when there was so much unemployment.

Nicole (30m 37s):

Yes, the depression was just such a difficult time and so much unemployment across the country and our own family, I know were struggling as well and leaving Oklahoma and going to California for work along with the other Okies.

Diana (30m 51s):

That’s exactly right. And the Dust Bowl you entered into that. It was really difficult time. And one of my great grandfathers suffered from mental illness, I think brought on by the stress of that era and ended up being in an institution for the last several years of his life. So I’ve often thought about that, how difficult it would have been for, especially these men who are trying to provide for their families and for the women who were trying to put food on the table. My dad tells stories about how they would only have meat if they went out and hunted and ate squirrel and possum, all sorts of things. So I think, oh my grandmother, having to try to figure out how to feed her family was a difficult time and it’s well worth researching it and learning more.

Nicole (31m 36s):

Yeah. You know, when we were talking about the American Guide Series about people traveling and this Federal Writers’ Project, it reminded me of the Green Book. Did you guys talk about the Green Book and in your class about how many Black Americans during the time of Jim Crow laws had their own book that told them where they could go to find restaurants, that they could stop that during this time of discrimination,

Diana (32m 2s):

We didn’t because it wasn’t a government record, but that is a great correlation. That is really interesting.

Nicole (32m 8s):

Yeah. The book is available online and I had seen it shared before, but it’s an interesting thing that you can also look into and research different issues of it to see if your family might’ve used that it was published by Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1966. And I will share a link in the show notes, so you can read more about it. But the article in Wikipedia talks about the discrimination that African-Americans experienced on the road and having to find gas stations that had bathrooms for colored people as they put it back then. And I’m just thinking about how difficult that would have been to take a road trip. Although it does talk about how they often preferred to use their own cars since public transportation had so much discrimination.

Nicole (32m 56s):

So it is a window into the time period. And it can be an interesting part of your historical research for your ancestors of this era.

Diana (33m 4s):

Wow. That is really fascinating. I’m glad you thought of that.

Nicole (33m 7s):

Well, that was good. Thank you for sharing what you learned in this part of your course. And we will come back next week with one more episode about African-American research specifically in government documents. So we will talk to you guys again next week. All right. Bye bye everyone.

Nicole (33m 59s):

Bye. Thank you for listening. We hope that something you heard today will help you make progress in your research. If you want to learn more, purchase our book Research Like a Pro a Genealogist Guide on Amazon.com and other booksellers. You can also register for our Research Like a Pro online course or join our next study group. Learn more at FamilyLocket.com. To share your progress and ask questions join our private Facebook group by sending us your book receipt or joining our eCourse or study group. If you like what you heard and would like to support this podcast, please subscribe, rate, and review. We hope you’ll start now to Research Like a Pro.

Links

RLP 121: African American Research Part 1

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Enrollee Records, Archival Holdings and Access

American Guide Series – Wikipedia list

The Green Book – Wikipedia article

Study Group – more information and email list

Research Like a Pro: A Genealogist’s Guide by Diana Elder with Nicole Dyer on Amazon.com

Thank you

Thanks for listening! We hope that you will share your thoughts about our podcast and help us out by doing the following:

Share an honest review on iTunes or Stitcher. You can easily write a review with Stitcher, without creating an account. Just scroll to the bottom of the page and click “write a review.” You simply provide a nickname and an email address that will not be published. We value your feedback and your ratings really help this podcast reach others. If you leave a review, we will read it on the podcast and answer any questions that you bring up in your review. Thank you!

Leave a comment in the comment or question in the comment section below.

Share the episode on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest.

Subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, or your favorite podcast app.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive notifications of new episodes.

Check out this list of genealogy podcasts from Feedspot: Top 20 Genealogy Podcasts

Leave a Reply

Thanks for the note!