Today’s episode of Research Like a Pro is about timelines and analysis. Learn about this second step in the research like a pro process. This is a replay of episode 114, with new commentary at the beginning by Diana and Nicole. Nicole shares Airtable timeline column headers. We talk about Diana’s second great-grandmother, Nancy Briscoe, who Diana researched as part of a 14 Day Mini-Research Like a Pro challenge.

Transcript

This is Research Like a Pro episode 185, Revisiting Timelines and Analysis Again. Welcome to Research Like a Pro a Genealogy Podcast about taking your research to the next level, hosted by Nicole Dyer and Diana Elder accredited genealogy professional. Diana and Nicole are the mother-daughter team at FamilyLocket.com and the authors of Research Like a Pro A Genealogist Guide. With Robin Wirthlin they also co-authored the companion volume, Research Like a Pro with DNA. Join Diana and Nicole as they discuss how to stay organized, make progress in their research and solve difficult cases.

Nicole (41s):

Let’s go, hi everyone. Welcome to Research Like a Pro.

Diana (47s):

Hi Nicole, and hi to everyone listening. We’re excited to continue our revisiting the Research Like a Pro steps. Last episode, we talked about research objectives, and today we’re going to talk about revisiting timelines and analysis, and we’re going to revisit an episode that we did 114, but we’re going to come back at the end and give you some of our new insights, especially since we talk about Airtable. And we’ve been using that for quite some time now and have all sorts of fun, new ideas.

Nicole (1m 21s):

Yes, today our example and this episode was about Nancy Brisco Frazier. And we kind of go through in the episode, some examples from her timeline of analyzing different pieces of information, like whether or not she was a firsthand witness of certain events like in the civil war pension file. And so it’s a good chance to think about analysis and source evidence, information labels, and those kinds of things.

Diana (1m 49s):

All right. Enjoy the episode.

Nicole (1m 53s):

Okay. Well, today’s subject is revisiting timelines and analysis. This topic is kind of the stage where you gather everything that you know about your project or your objective that, you know, you’ve already found in the past. And you just review everything that you have and gathering all the known information, then organizing it into a timeline or a chronology, and then really analyzing each of your pieces of information to understand the source, the information and the evidence to see what level of quality your information is.

Diana (2m 25s):

I love this process and I love this step in the process. It is so fun to get out all your records and go through them again and look at them with a new eye. I just find that with every little bit of experience and education, I get, I learn more about the records and I see more in the records. And I think this is what is the real value of having someone else look at your research, or when a client gives me a project and often they’ve been working on this brick wall of theirs for years and years, but when I go through it and I do the timeline analysis, I just find so much more there than they ever dreamed. And that’s just because of more experience.

Diana (3m 6s):

So as genealogists, the more we learn more experience, we have, we look at our things with a really fresh outlook, and that’s the value of doing this, this timeline analysis. You can do a chronology or a timeline. And so I’m just want to talk a little bit to the differences there. A timeline is done in a spreadsheet and you have a column for the date, the place, the source citation, and then concrete each of the parts of evidence analysis, the information evidence, the source, any notes that you have, imagine a spreadsheet, and it’s all right there in front of you and you can color code it.

Diana (3m 47s):

You can do whatever you want to really show the information. So it’s pretty succinct. And I like that because I want to see everything kind of at a glance, but another way you can do this analysis is in a chronology. And that would be something that you do in a Google doc or a Microsoft word document. And you would just list the date and then you would go into more detail. Think of it more as a narrative form, where you would discuss that source in detail and the information and the evidence. It holds. Some people really like having some real description of each piece that you want to have in your chronology.

Diana (4m 29s):

So it just really depends. And if you’re just new to the process, you could try both and see the difference. See if you like one over the other and just kind of explore what works best for you and your research.

Nicole (4m 43s):

I really like the chronology and I find that it’s helpful to write out a lot of analysis on some of my more difficult cases. So that one is really helpful for me. And actually sometimes I’ll make both, I’ll put a simple timeline up so I can kind of see visually the look of the timeline and the flow of it. And then I’ll write out all the details and all my thoughts and analysis in a longer chronology. And so I’ve done that before, and that can be helpful. You know, if it’s something that you’re really planning on doing a lot of work on, it’s helpful to do a very thorough starting point analysis like that.

Diana (5m 19s):

Another thought is that if you are writing that narrative about each of the sources, you could take portions of that to use for your research report, where you’re dispensing that source. So it’s like doing a little bit of preliminary writing as you go. And a lot of people like that idea of writing as you’re going through this process. So that’s something that you could also try, you know, thinking that you maybe could use this in your future research report.

Nicole (5m 48s):

Yes. One thing that I just thought of that a lot of people who are new to research like a pro wonder is should they make source citations for everything in their timeline? Yes, you should. But if you haven’t ever done source citations and you’re just making your timeline, and this is kind of your first step, you can wait until you get to the source citations step to practice and learn how to do that. And then the assignment we have you do is go back to your timeline and put in all the citations. So what you need to do in your timeline is make sure you put a link to where that source is located online, or just describe where it is in your file folder so that you can easily get it again. When you make the citation, obviously it’s best to do the citation. If you know how right when you’re doing your timeline, but if you don’t know how yet, then you’ll come back to that later.

Diana (6m 34s):

Right? And I put our citations a little bit later in the process because I wanted people just to have fun with this. And I thought, oh man, if we puts our citations right away, that might scare off a lot of people, right. But if you’ve already done a lot of the process and then you come to that, you’re invested in it and then you’ll be able to kind of embrace the source citation. So there’s a lot of different order. You can teach this process, but you have to just do one thing at a time.

Nicole (7m 1s):

All right, let’s talk about why we’re doing a timeline or chronology. So the purpose behind doing this step is to review everything that’s known about your research subject and gather everything that’s already been done about them. So you’re going to look in your home sources, your family tree that you’ve created. And you can also look at other people’s published online family trees, or other published sources that you know about. Like if you know that your aunt has a book about this side of the family, you’re going to want to check that if you can, when you do this phase of gathering, what’s already known, this can become a little tricky though, as you start gathering, what’s already known because you might be tempted to start doing actual research about unknown information and trying to find people who’ve found out stuff.

Nicole (7m 45s):

And that can just go into your research plan. But if you already know that your aunt has that book, you can try to get it and put it in your timeline now. So don’t go overboard here. You want to gather, what’s already known that’s, you know, within your access now and whatever you can’t access now, or you have ideas to research, that’s going to go into your research plan. So I like to check ancestry, published trees, to see what other people are found and family search tree. And sometimes I will integrate some of their conclusions or the sources they have attached to that person as well, if it seems to be correct. And then I’ll just analyze that as an authored source in my timeline,

Diana (8m 25s):

I think those are great ideas. And I really liked what you said about being careful not to start researching and going down those rabbit holes, but just to put in your notes that this is something that could be future research could go into the research plan when you get to that step. So we get a lot of questions about this idea of a timeline from people. And one of them is if we could just generate a timeline from ancestry or family search or from your personal genealogical software. And you know, our answer really is no, because the whole purpose of this is to help you to understand your information better.

Diana (9m 9s):

If you’re just using a timeline generated by software, it doesn’t make you look at it any differently, really. So in this process of actually looking at your things again, and then analyzing the sources in theater and the information you create a solid foundation for what you know, and you get a lot of ideas about where you can go further with this. If you haven’t looked at this research much or lately, you will have likely forgotten all those little nuances that are going to help you in making a research plan. So you really want to do this yourself.

Nicole (9m 48s):

I agree. I think it’s really helpful. All right, let’s talk about where to create your timeline or chronology. So if you’re doing a chronology, you’re just going to create it in a document word, Google docs, whatever you’re comfortable with, but for the timeline we suggest using a spreadsheet because it really allows you to sort your data and have more control over it. Obviously you could also create a table within a document, but I’ve found that those are a little bit clunkier and just have a little less options for sorting and for formatting. So we really prefer using a spreadsheet like Excel or Google sheets to create your timeline. And of course we love Airtable now as well.

Nicole (10m 30s):

And air table is a great option for creating your timeline too. Especially if it’s a DNA project and you’re creating a timeline for your research subject or hypothesized ancestor, and then you’re going to be doing DNA matches with it. Then it makes sense to just put everything all into one Airtable base,

Diana (10m 49s):

Right? I had gotten, so I really like to have everything together and that one Airtable base, it works perfectly to keep it all in one place and it eliminates multiple files. Well, let’s talk about how much you should include in the timeline. This is another common question, because when you’re doing this process, you will have defined an objective. And sometimes people want to know if they should just put in the information that goes with that objective. And my thought is always, you want to include everything you can about the person, because how are you to judge whether that piece of information won’t work with your objective.

Diana (11m 28s):

I mean, we find answers to relationships in land records. And if we had excluded putting in some of those different types of records into our timeline, we might have missed pieces of information that are really going to help us. So you really want to include everything that pertains to your research subject and their life. We have this phrase in the genealogy world of reasonably exhaustive research, where we want to examine all possibly relevant sources. So even if there is a source that was created after a person passed away, it was a source for one of their children’s records, but it pertains to the ancestor that could be relevant to the person’s birth.

Diana (12m 14s):

And I think of the example of a woman, and you’re trying to figure out her maiden name and it’s found only in the death certificates of her children. What would that go in her timeline? Of course, that would, because that is going to provide evidence for her maiden name. And just because it was created after the time span of her life doesn’t mean we would not include it. So don’t limit yourself in this really think of everything that could help think a little bit outside the box. What else could there be out there that could give you information about your ancestor? Like I said, children’s death certificates or a pension application that was done by the widow or perhaps children think about what you’ve got for this family that could help with identifying and learning more about your research subject.

Nicole (13m 10s):

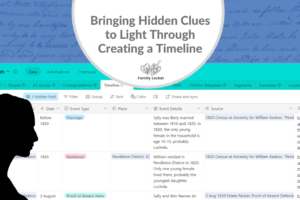

Yes. I think sometimes we want to just build a timeline based on the person’s early life and hope that that’ll be enough because if we go forward to their vendor, their life and their children, that adds a lot of data, but then that might give us a valuable clue that we would have missed before. So the more that you can knew the better, especially if you have already gathered a lot of information about this family, all right, let’s talk about color coding the timeline. This is something that a lot of people find really useful, and Diana has color coded her example, timeline of Nancy Briscoe. So some reasons why you might want to color code the events in your timeline art. So you can quickly identify what you’re looking at.

Nicole (13m 52s):

This is kind of a visual cue that, oh yeah. This green event is a residence and all of these green ones, these are places where they’ve lived. These are census residences and then pink, that’s a marriage. Okay. So I can see the marriage really quickly. And then the birth is color coded yellow. So I have several different conflicting dates that were given by various sources for her birth. So I’ve color coded all those yellow. So I can just remember that all those events in the beginning are all pieces of information about her birth. So the color coding can be really useful and fun.

Diana (14m 26s):

I like color. And I always say, if you can use color, why not use it? It’s easy to do. And it’s so fun. It just adds a little bit of interest to our eyes rather than a white screen all the time. So let’s talk about what you actually do with this timeline analysis. And that is when we look at the source information and evidence. So let’s talk about the source first and sources and three types. We have original sources, derivative sources and authored sources. So there’s the column in the timeline. And if you’re doing a chronology, you would just add this for the source. So we first look at that and really think about when this source was created.

Diana (15m 14s):

And if this was the first time that information was recorded now in my Nancy Frasier analysis, her timeline, Nancy Brisco Frazier, like Nicole said, I have several entries for her birth as written in the census records. And I’m sure a lot of you listening can relate to this, that there are so many different entries for her birth year. She was born either in 1845, 1847, 48, 1850, 1849. You know, I’ve got a range there of about five years. And so when I look at all that information, I want to think about how that information can be used in researching her life.

Diana (16m 6s):

So a census record is an original record. It’s the first time information was recorded. So when the census taker came to the household in 1850 and asked, who was living in your household and how old are they and then recorded that. And then we are looking at the image of it that is generally at original source. Sometimes in the census records, you can see that they were perhaps recopied for a state copy, or there’s something different with that. But you take a look at that and see if you can see that they handwriting is the same enumerator and that it looks like that the households were recorded in the order they were visited.

Diana (16m 49s):

We just have to look carefully at our sources. So another example in the timeline is Nancy Frazier’s application for a pension. Her husband had died. And in Oklahoma, when they passed the pension law in 1915, she applied for a Confederate pension because of his service in the Confederacy. And that application has been digitized. It’s in beautiful color on the Oklahoma website. And it is an image of the original application. And you can see the different handwriting of the different clerks helping to fill out the information and she was providing the information.

Diana (17m 33s):

And so that’s an original record that was created at the time she applied for that pension. And then we also have on her record, a headstone photograph, and this is on find a grave that headstone was likely created the time of her death by her children. Sometimes headstones are created much later, but it is an original source. And we would have to look at the information and analyze it. But a photograph of a headstone is original. Then we have derivative sources which are copies or reproductions of the original. So on Find a Grave we also have memorials.

Diana (18m 18s):

Memorials can be derivative, or they can be authored. They can be a mix and Find a Grave is a good example of that. If someone is just simply copying off of that, headstone the dates and the names and whatever information there, that would be a derivative because they’re making a copy of the original headstone and putting that on, Find a Grave as a record. Sometimes those memorials are authored, however, because the person creating those is using other information. And I see this a lot where the information that someone has put on the Memorial is different from the headstone. So I always wonder, okay, well, where did that information come from?

Diana (19m 1s):

Did you get that from a death certificate, which differs from the headstone and we don’t always know why someone would have different dates that are on the headstone. So we just look at it carefully and analyze it, trying to decide what could be the most correct. Now, besides derivative, we have the authored source and this is where we have a mix of the original and derivative, it is authored by someone. We may know who that is, or we may not know. And an example of this would be a county history. In a county history we often have the author reporting on maybe early settlers or perhaps someone sent in a biography of their family to be included in that county history.

Diana (19m 53s):

And we could have some derivative sources where the author is maybe gone out and gotten some cemetery headstones and transcribe those and put those into the county history. It can be a huge hodgepodge of different facts, so it can have a good mix of original and derivative. And we call that authored. Another good example of authored sources are family trees, where people have taken a mix of all different kinds of records and created this new source, this family tree that has a mix of different types of sources.

Nicole (20m 33s):

Great. So as you review, the three types of sources are original, derivative and authored. An original source is the first time information is recorded. A derivative is a copy or a reproduction translation or transcription of that original, and then authored as a mix of the two. Okay. Now let’s go on to information. The information item that you’re specifically looking at, and there might be several within a source. And usually there are, and you can’t figure out what type of information it is until you’ve determined who the informant for that information was. The informant is just the person giving the information to the person, recording it.

Nicole (21m 14s):

If it’s primary information, then that information was given from a witness to the event. It’s a firsthand account. So in Diana’s timeline for Nancy Briscoe and example of primary information is when Nancy gave information about her marriage on her pension application. She was present at that marriage and she remembers it, so she is a primary informant. Now she didn’t actually remember the date of her marriage, she just put the month in the year, right?

Diana (21m 45s):

Right. She put October, 1863.

Nicole (21m 46s):

So even though she didn’t remember the exact day, or, you know, maybe she just didn’t put the exact day, we don’t know, she’s still a primary informant because she was there at that marriage. And so we can also analyze the informant’s reliability and their memory at the time they’re giving the information, but that doesn’t change the fact that it was primary information. Another example of primary information is in Diana’s timeline for Nancy’s death date. So in the pension file that Oklahoma has for Nancy Briscoe Frazier, that file contains a letter written by her son, Ed Frazier, which had Nancy’s death date. And he was telling the pension board, she died on this date.

Nicole (22m 31s):

So that’s primary information because he was a witness to when she died, because he was there with her. Now, obviously the difference between firsthand accounts and people who are not witnesses is that they heard it from someone else. And so that makes the information secondary. So in the timeline, the example of Nancy birth date from the pension application, that is secondary information because even though she was present at her birth, she was not a reliable witness to her birth because she was an infant. So that was told to her, you were born on such and such date. And that was something that she was told.

Nicole (23m 10s):

And then she shared as secondary information on her pension application. Another piece of secondary information from the timeline is when Nancy reported her husband’s military service. So I did think about this a little bit, because she might have been a witness to his service. If she knew him at the time he went into the military and she saw him, you know, with his unit, maybe she could have been a witness to it, or maybe they got married afterward and she didn’t know him at all. Like she had never met him until after. And he told her about his military service and therefore she was not a witness to it. And she just heard it from him.

Nicole (23m 50s):

So what do you think, Diana?

Diana (23m 54s):

I was thinking that it was secondary, but as I did more research on her, you know, they got married in 1863 smack dab in the middle of the civil war and her husband, Richard Frazier joined Captain Clanton’s company, which was organized right there in the area they were living. So I have a feeling that she knew very well all about the company that he joined because her mother was a Clanton and I’m guessing this was probably an uncle or a relative. So she very well could have been a firsthand witness of his service.

Nicole (24m 29s):

And I think she gave really specific information all about which company and everything, right?

Diana (24m 36s):

Yeah, she did. She talked about how first he was an infantry and then he was in the cavalry and he was in Marmaduke’s division. So there is specific information there, which makes me think she was probably more of a firsthand witness to that than we might’ve thought now contrast that with my other great-grandmother Isabel Royston and her husband served in the Confederacy in Alabama and she was in Missouri. And so they didn’t get married until they were both in Texas. So she would not have been firsthand. She would have definitely been a secondary informant on her pension just because he told her that he was serving in Alabama.

Diana (25m 19s):

So I think those are two good examples of different scenarios

Nicole (25m 23s):

For sure. And if I remember right, Isabelle didn’t know anything about Robert’s company at all, she just said he was a sharp shooter.

Diana (25m 32s):

Exactly.

Nicole (25m 32s):

Yeah. So sometimes you can look at the information that’s being given and that can help you determine whether or not it was probably primary or secondary if you’re not sure, but sometimes we don’t know. And that brings me to the final category of information, which is undetermined. You can’t tell who the informant was for sure. Or you can’t tell if the informant was an eye witness to the event, but you can always make an educated guess. Like I was saying, if you look at the information and compare and contrast it and correlate it with the other information that you have and try to figure out how accurate it was and make an educated guess. So for all the census information, except for 1940, we don’t know who the informant was for the family information names and birth dates and things.

Nicole (26m 15s):

So we just have to kind of guess usually the informant was supposed to be the head of the household, but the enumerator was able to ask someone else if the head of household was not available. So sometimes you can kind of figure it out. Maybe if all the information seems a little off, then maybe it was a farmhand giving me information who didn’t know or something like that. So on the census, all that information is undetermined except for the residents, which is primary information. The enumerator came to their house and witnessed where the family lived at that point in time. So the fact that they lived in 1850 in a certain location is primary information.

Nicole (26m 58s):

Another example of undetermined information is a headstone. So the headstone itself, if you have an image of it or you see it in person is an original source, but the information on it usually doesn’t say who gave that information, it doesn’t say this headstone was created by so-and-so. Although sometimes it does, which is so nice when it says erected by so-and-so, but even if it was paid for and created by one of the children, it doesn’t mean that child was the one who was saying the birth and death date probably was, but you still don’t know for sure the birth is probably almost certainly going to be secondary because if a person lived to an old age, the people who are still around making the headstone, probably weren’t an eye witness to their birth, unless they are older than the person who died.

Nicole (27m 45s):

For the death date, that one could be primary, but we don’t know, so it’s still undetermined, but the person who created the headstone maybe was a witness to the person’s death. And so it could be primary.

Diana (27m 58s):

Okay. So I have a really good example from my latest project that I did. So, you know, those histories or biographies or genealogies that have been written like sometimes a really long ago, and you have no idea how accurate the information is. Well, I had one of those that told all about this family, and I thought, I’m just going to go look at the beginning and see if I can figure out how reliable all this information is, because this was obviously an authored source. You know, those genealogies they’ve gathered up sources, right? So I looked at the beginning, this was digitized on ancestry and it was written in 1885 that’s when it was published. And then it had this note about the author and it talked about how he had scoured libraries and records and various repositories.

Diana (28m 45s):

And he had talked to all sorts of different family members to get the information. And then he named the specific person who gave the information for the family I was researching. And it turned out that he was an older brother of this research subject and he would have known him really well. So it was so fun because I was actually able to figure out an informant and to figure out that most of the information was primary information out of that genealogies.

Nicole (29m 14s):

Oh, wonderful.

Diana (29m 15s):

But you know, you had to scroll to the beginning and then really read all that front matter. So if you have a family history, it’s really worth doing some exploration, which is why we want to do this analysis on our sources. Yes.

Nicole (29m 27s):

And that is a really good point that to do source analysis, we really have to understand the source and try to figure out who created it sometimes, especially with books, that means like looking through the whole book,

Diana (29m 43s):

It does, it does. And even with microfilm, a lot of times I will have a collection of, let’s say marriage records. And sometimes you have to scroll right to the beginning of the microfilm or the digitized microfilm that we usually use now. And sometimes there’ll be some explanation there. We really have to do some good detective work on our sources to understand the information in them, it all goes together.

Nicole (30m 8s):

Yeah. And sometimes I was on like microfilms or books of church records, at the beginning it will tell you the name of the person who was recording it and their system, you know, the pastor or whatever would do the burial ceremony and then record it. Then you can kind of see, oh yeah, this is a firsthand account because he was there at the burial.

Diana (30m 30s):

Exactly. I think one of my most interesting cases involves a book where a woman, it literally said at the beginning of the book that this woman looked out her window every day and wrote down all the happenings in the little neighborhood, which totally cracked me up. And then she had a scrapbook of all the newspaper clippings. And so, so that was the source, this book of this woman recording things that were happening and then the newspaper clippings to back those up. So that’s the fun about genealogy. We never know what we’re going to find.

Nicole (31m 4s):

That’s great.

Diana (31m 5s):

All right. So we’ve talked about the three kinds of information, primary, secondary, and undetermined, depending on who was the informant. Now we’re going to talk about the three kinds of evidence we have direct, indirect and negative evidence. And evidence is all about the research question or the question that is answered by the information. So in direct evidence, the information answers the question directly. So we have the question for my Nancy Briscoe. When was she married? Well, we have direct evidence in that widow’s pension application, because it has a question.

Diana (31m 47s):

When were you married? And she records there that it was October of 1863 doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s accurate. It’s just directly answering the research question. It doesn’t have to be complete information to be direct evidence. Nancy obviously didn’t quite remember the day she was married, but she remembered October. Well, that could give me a clue that maybe she just kind of remembered it was in the fall, you know, that portion of the year. And so if I were later to find conflicting evidence that said maybe November or September, I could correlate and resolve that by saying she didn’t have a specific date.

Diana (32m 31s):

And maybe she was just remembering the time of year because she was, you know, much older at the time she was giving that information. But it directly stated the answer to when she got married. Now indirect evidence is where the information provides a clue that we have to combine with other facts. So for that same question of when was Nancy married, we could turn to the census to get some clues. And often we have to do this when we do not have anything for a marriage record, we often look for when the first child was born and then we subtract a year. So with Nancy’s case, we have her in the 1870 census, the first census where she is married to her husband, Richard and their first child was born in 1868 as recorded on that census.

Diana (33m 23s):

So I have her in 1860 single. So we would think if we didn’t have a marriage date that she could have been between 1860 and 1868 and often, you know, I’ll do an estimation of something like 1867 because the child was born in 1868, but it is indirect evidence because that question was not asked in the census, like when did you get married? Just ask how old is this child? And so I’m having to do some thinking through and using the clues to figure something out. Now we can have negative evidence, which is the absence of information.

Diana (34m 3s):

And so for that same question of when Nancy was married, if I looked at her father’s household in 1870, and she was not listed there anymore, and she had been up until then, then that would be some information that she was probably married. And her absence of being in that household could be used as negative evidence. Now we always have to use indirect and negative evidence together with a lot of other evidence. It doesn’t just stand on its own. So what are some other scenarios if she wasn’t in her father’s household in 1870, or maybe she wasn’t married, but she was just living with another family and working for them.

Diana (34m 48s):

She was living away from home. So she wasn’t in the household, but she wasn’t necessarily married. So we use negative, which is a form of indirect evidence and indirect evidence with lots of other moving pieces. And we use those to provide proof of a fact. And this is quite honestly why we have to write up our research. If we are using all the indirect and negative evidence to prove something, it doesn’t show up just putting it into a tree or on, you know, FamilySearch or Ancestry. People can look at that and not understand anything, but when we write it and we correlate it, that is where we can actually establish proof, which is why it’s so fun to be able to take all these pieces and put them together.

Diana (35m 36s):

Yeah. And that’s why we have the written

Nicole (35m 39s):

conclusion portion of the genealogical proof standard, because we can’t really say that something’s proven unless we are able to write it out clearly and logically with documentation. Wow. We went through all of the analysis. And so now after you create your timeline, you can have columns for a source information evidence, and you can go through and analyze each event or piece of information from your timeline and see if it’s an original source or derivative or authored and what kind of information it is. And then what kind of evidence, and in the study group, we usually have people who ask the question when you analyze an event in your timeline, and you’re trying to figure out what kind of evidence it provides.

Nicole (36m 22s):

Do you look at your research objective that you’re doing for the project to decide if it’s direct evidence for that question? Or do you look at the event itself and say, this provides direct evidence for the residents and the names. So Diana, what do we tell them?

Diana (36m 39s):

Well, I really like to analyze the evidence just for the specific event that makes it a little more simple. So if we’re looking at a marriage record, we are going to say, yeah, that’s direct evidence for that marriage because there’s a record. And it answers the question of when did they get married? And if we’re looking at a census and we’re trying to decide relationships that aren’t clear, we might want to say it’s indirect evidence for a relationship. So I like to just do the evidence analysis specifically for the event, each event in the timeline.

Nicole (37m 16s):

Yeah. When I did my Lucinda Keaton timeline, my question was who is the father of Lucinda Keaton? And then all of the things on my timeline, didn’t tell me the name of her father. So I just put indirect for all of them. So that wasn’t that useful to me. So I think what it is is that you can’t apply a specific label to each event as being direct or indirect or negative, because there’s so many different questions you could be asking of that information. And each question that you asked could give you a different type of evidence, right? So it’s a little bit easier to do this in a chronology or in something where you write out more discussion, you can say, well, this provides direct evidence for the names of the people in that household, but it provides indirect evidence that their relationship is parent child because it’s prior to 1880 and it doesn’t show, you know, if this is the parent and this is the child that just shows they’re all living in the household together.

Nicole (38m 11s):

So you can really kind of talk it out and figure out what’s direct, what’s indirect. And then you’ll also find some negative evidence too. On one of my timelines that I did, it was glaringly obvious that after 1830, then man did not live in that place anymore because he was absent from the census and absent from the tax records. And then there was a land sale of his heirs. And so I saw a big piece of negative evidence that he had disappeared. And so I guess that he had died right about then. So I did put that piece of negative evidence in my timeline, but it was just kind of an interesting entry on the timeline because it was kind of by itself. And it was based on a few different other sources, right?

Diana (38m 56s):

And it can be kind of tricky getting all of these things clear in your head, the source information evidence. So what I just like to tell anyone who’s trying this process, trying to do the timeline, do the best you can. And as your understanding grows, as your experience grows, it will get easier. You’ll you’ll get better. The important thing is just to really think through carefully the information that you’re using for your genealogy, this will help you to really clarify some things, look at it in a new way. Don’t stress too much about trying to decide if you have everything analyzed perfectly.

Nicole (39m 33s):

Yeah. The point of doing the analysis is to get the best information. So if you find that you have a lot of derivative records, then you’re going to want to try and find the original source. And if you find you’re basing a lot of conclusions on secondary information, you might want to try to find some records where the informant was an eyewitness, if possible, right?

Diana (39m 54s):

That’s a great point. Sometimes this really points out that you are using just a lot of authored sources or derivative sources, and you got to really go to work on finding some original, better sources for the information.

Nicole (40m 8s):

And if you find that your evidence is a lot of it going to be indirect for your question, then just get ready to write a lot. Because the more you write, the more you can weave in your indirect evidence. Right?

Diana (40m 22s):

Right. Well, it’s been fun to revisit evidence analysis and think through all those categories. Again, it’s always good to go back to the basics.

Nicole (40m 31s):

So as you heard in the episode, we talked a little bit about how Airtable is a good tool for timelines. And it’s a great place for keeping all of your tables and data in one place so that you can have your timeline. You can have your research log all in one Airtable base. So one thing that I would add to that discussion is that you can color your Airtable timeline, and the way you do it is by either using the single select or the multiple select field types. And both of those have colored options. So you can go in there and put different locations. Like if you put in Ireland, England, and Germany, then you can have those all be colored, different colors. Or if you have different counties within Alabama, each one of those counties can have different colors.

Nicole (41m 15s):

So it doesn’t color the whole entire row, but it does give that one column or field in the row a color. So if you like coloring things, that’s totally possible in Airtable. Another thing we do with the timeline is to have colored event types. And Diana talked about this in the episode about sometimes it’s nice to have different colors for all the births information and like a different color for all of the residents information so that you can see at a glance what event type you’re looking at in the timeline. So you can also do this with Airtable and the single select field type. And you can just select this event. This row is a residence.

Nicole (41m 56s):

And so it’s blue. So that’s a fun thing you can do in Airtable.

Diana (42m 2s):

Yeah. I love the colors for some reason when, just because I’m sitting at a computer all day, having a little bit of color in my life makes things so much more fun and Airtable is really fun to fill out. So I have to admit that I like have

Nicole (42m 17s):

So in my Airtable base, I have a table for the timeline. And these are the columns that I use now event, which is the primary field where you can just kind of describe the event in three or less words, like 1850 census for John. And then the date, which is a single line of text feel type and not the date because I like to put it in genealogical date format, which most computers don’t do. So I just use single line of text. And then, because it’s not in a date format, you do have to sort it yourself, which is fine. I usually just insert the events in the place where they belong in the timeline, or you can drag and drop the rows into the right place.

Nicole (43m 3s):

And then there’s the type. And this is where I do a colored event type like birth residents, marriage, death, immigration, et cetera. And then the next field or column is place. And I also do a single select field type with this so I can have colored option. So I can see where the event occurred at a glance by color. And then details is a long text field source citation also is a long text field with the rich formatting option turned on so that I can use italics. Then the next column is a URL pointing to where that record is located. If it’s online and then notes, long text paragraph field, and then FAN club, which is a link to the FAN club table, so that I can put in any people that are also present on that record or at that event in ancestors’ timeline, so that I can get an idea of their FAN club and then attachments, where you can upload an image of the record and then source information and evidence columns for analysis.

Nicole (44m 2s):

And I, I played around with doing this as like a single select or multiple select. So you can just choose from the list of different labels, source, labels, and classifications. But then I decided I really prefer having them be long text fields where I can type out kind of my thoughts about the analysis, because it really isn’t that helpful to just say this source is authored. It’s more helpful to say this is an authored source because, and this author didn’t seem to use source citations. And so you can kind of comment on the quality of that author, because if they’re a really good author, then maybe it would be a way to hear a piece of evidence. But if it was a lower quality author that didn’t cite sources and maybe seem to be relying on oral legends, then you would want to put less weight on that evidence.

Diana (44m 49s):

Yeah. I really like to have that be more text also rather than just a single select field, because I like to type some ideas out and some thoughts out. And I wanted to talk a little bit about the evidence column, this whole idea of trying to categorize evidence. And one of the things we need to realize that we really classify evidence at the end of the project when we’re writing it, when we’re assembling. And this is something that Tom Jones teaches. And if we try to think about what evidence something is giving prematurely, it could cause us to go off in the wrong direction or have bias, but it’s good to practice and think about the evidence that a piece of information holds.

Diana (45m 32s):

And so what I like to do when I’m looking at the source is thinking about the evidence, a particular piece of information gives. And so, you know, I’ll say something like the census provides direct evidence of the residents of the household. It’s good for us to use our brains and be thinking about what pieces of evidence we can gather from a source. And, you know, I’m working on a project right now where I’m going to be using a lot of negative and indirect evidence. And I can’t really put that in the timeline. You know, the lack of this person being in the census is negative evidence that, that comes together when you’ve done all the research.

Diana (46m 12s):

But do, you can put some specific things in there to get you started on your ability to analyze evidence?

Nicole (46m 20s):

Yes. For sure. And you can ask a question of each event and say, if my research question, where, when were these people married, then this authored source gives me direct evidence of that. Or this census record gives me direct evidence of that marriage date. But if you don’t have the exact marriage date and you just have a child’s birth, you could say this child’s birth gives me indirect evidence of the marriage date that they were probably married before this child was born.

Diana (46m 50s):

Right. And you can also say that with perhaps a household in 1850 with no relationships stated, and you could say, well, this is indirect evidence of a possible husband and wife and children, because you don’t know for sure if that really is the case or not, but you can make a note that that could be indirect evidence. It’s just to get us thinking about what we’ve confined in that source.

Nicole (47m 13s):

All right. Well, we hope you enjoyed listening to this episode about timelines and analysis, and we will talk to you guys again in the next episode.

Diana (47m 24s):

All right. Bye. Bye everyone.

Nicole (47m 26s):

Thank you for listening. We hope that something you heard today will help you make progress in your research. If you want to learn more, purchase our books, Research Like a Pro and Research Like a Pro with DNA on Amazon.com and other booksellers. You can also register for our online courses or study groups of the same names. Learn more at FamilyLocket.com/services. To share your progress and ask questions, join our private Facebook group by sending us your book receipt or joining our courses to get updates in your email inbox each Monday, subscribe to our newsletter at FamilyLocket.com/newsletter. Please subscribe, rate and review our podcast. We read each review and are so thankful for them. We hope you’ll start now to Research Like a Pro.

Links

RLP 114: Revisiting Timelines and Analysis https://familylocket.com/rlp-114-revisiting-timelines-and-analysis/

RLP Airtable Base – https://www.airtable.com/universe/expk5XjE2iXWeZTAU/rlp-study-group-2021

Research Like a Pro Resources

Research Like a Pro: A Genealogist’s Guide book by Diana Elder with Nicole Dyer on Amazon.com – https://amzn.to/2x0ku3d

Research Like a Pro eCourse – independent study course – https://familylocket.com/product/research-like-a-pro-e-course/

RLP Study Group – upcoming group and email notification list – https://familylocket.com/services/research-like-a-pro-study-group/

Research Like a Pro with DNA Resources

Research Like a Pro with DNA: A Genealogist’s Guide to Finding and Confirming Ancestors with DNA Evidence book by Diana Elder, Nicole Dyer, and Robin Wirthlin – https://amzn.to/3gn0hKx

Research Like a Pro with DNA eCourse – independent study course – https://familylocket.com/product/research-like-a-pro-with-dna-ecourse/

RLP with DNA Study Group – upcoming group and email notification list – https://familylocket.com/services/research-like-a-pro-with-dna-study-group/

Thank you

Thanks for listening! We hope that you will share your thoughts about our podcast and help us out by doing the following:

Share an honest review on iTunes or Stitcher. You can easily write a review with Stitcher, without creating an account. Just scroll to the bottom of the page and click “write a review.” You simply provide a nickname and an email address that will not be published. We value your feedback and your ratings really help this podcast reach others. If you leave a review, we will read it on the podcast and answer any questions that you bring up in your review. Thank you!

Leave a comment in the comment or question in the comment section below.

Share the episode on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest.

Subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, or your favorite podcast app.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive notifications of new episodes – https://familylocket.com/sign-up/

Check out this list of genealogy podcasts from Feedspot: Top 20 Genealogy Podcasts – https://blog.feedspot.com/genealogy_podcasts/

1 Comment

Leave your reply.