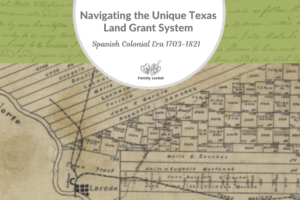

Today’s episode of Research Like a Pro is about how the Republic of Texas and State of Texas issued land to the thousands of settlers that poured in after independence from Mexico in 1836. We discuss the land application process, headright grants, colony grants, Texas statehood and changes in governance, preemption grants, and military land grants. We also discuss the Texas land survey system and how to find Texas land grant records.

Transcript

Nicole (1s):

This is Research Like a Pro episode 196, Texas Land Grants – Republic and Statehood.

Nicole (41s):

Welcome to Research Like a Pro a Genealogy Podcast about taking your research to the next level, hosted by Nicole Dyer and Diana Elder accredited genealogy professional. Diana and Nicole are the mother-daughter team at FamilyLocket.com and the authors of Research Like a Pro A Genealogist Guide. With Robin Wirthlin they also co-authored the companion volume, Research Like a Pro with DNA. Join Diana and Nicole as they discuss how to stay organized, make progress in their research and solve difficult cases. Let’s go. Hello everyone. Welcome to Research Like a Pro. Hi.

Diana (48s):

Hi, Nicole. How are you today?

Nicole (50s):

I’m good. How are you?

Diana (52s):

I am doing great.

Nicole (54s):

What’s new.

Diana (55s):

Well, I am then reading a fun article on focus, time for your work. I don’t know if anybody listening, ever feels like this, but you’re just getting started on maybe some good research or writing something up like a reporter history. And then you see an email comes in and then that takes you off. Totally takes you out of your focus time or your phone rings or texts comes in. And so that’s so appropriate to my life. Cause I need to have focus time to write blog posts or you know, to do client work. Anyway, this article is great. It’s by Drew Smith, it’s in the Association of Professional Genealogists Quarterly.

Diana (1m 37s):

So the APG Quarterly, and it just has so many good ideas for focus time. One of them I really like is guarding your focus time talks about calendaring it. So like decide when is the best time of day. Some of us are morning people. Some of us are night owls. You know, when do you work best? When is your focus time and then to calendar that and not let any other things take priority and turn off notifications, turn off your email. You know, don’t have your phone in the same room, you know, different things that can cause our distractions. It’s a good article. It’s things that maybe we should already know in the back of our mind, but we forget. And it’s nice to have somebody pointed out to us.

Nicole (2m 18s):

Absolutely. I really struggle with finding time to work that’s uninterrupted as well. And one thing that I’m trying to work on is guarding my time. Like you said, when I do have that focus time and making sure that I’m not doing tasks, that don’t require that focus during that special time where the baby’s napping and the kids are at school,

Diana (2m 40s):

Right? Because there are some tasks, like if you’re answering an email, it may be takes five or 10 minutes of time. And you can do that in between taking care of your kids when they’re home from school. But when, once you get going on a project, you really have to focus and make connections in the records that you’re writing reports. So yeah, kind of taking a look at your schedule and when you can do that, the best is super important.

Nicole (3m 7s):

Yeah. It’s something I have to reevaluate often. Well, we thought it would be fun to talk a little more about the NGS conference coming up. So they have this wonderful PDF conference schedule and it talks about the different tracks of each session and the different levels so that you can kind of put together a schedule that will work for you. That, that has the classes that are, you know, aligning with your interests and the different levels of the lectures are beginner, beginner, intermediate, intermediate, intermediate, advanced, advanced, and all levels. So there’s different labels on the classes like that. And then one thing that’s fun is that every day there’s several different tracks of classes so that you can kind of follow that track and learn about a specific topic.

Nicole (3m 55s):

So for example, on Wednesday, there’s the BCG skill-building track. And then there’s the Eastern states track. And so you’ll have classes that are in that same vein or topic for several hours in a row. And then another track is immigration land and maps, methodology, native American records and repositories Western states writing. So then you’ll get several classes on those topics and then you get some new tracks on Thursday. So some of them are the same, but then you also get African-American on Thursday and DNA and Europe and middle Eastern track. There’s a Jewish track as well.

Nicole (4m 35s):

Then on Friday, some of the additional tracks are the Chinese American track and Hispanic and Latin America and westward migration and technology. So check out the NGS conference schedule. And the conference is may of this year, May 24th to 28th, 2022 in Sacramento, California. So we look forward to seeing you there.

Diana (5m 1s):

Absolutely. It’s going to be so fun to be back in person or crossing our fingers that that happens. And we can see people’s faces in person and not on Zoom. Not that we don’t mind Zoom, but it will be fun to be in person.

Nicole (5m 17s):

Yep. Well, let’s continue on our fun Texas Land grant series. Today we’re going to talk about the Texas Land Grants during the Republican statehood. So If you have an ancestor who came to Texas, then you’ll want to understand kind of this history that we’ve been going over and the jurisdictions so that you can find the records. And as you know, we’ve been doing a series of discussions starting with the Spanish time period, the Mexican Era, the Republic and Statehood era’s. So we really want to learn about our ancestors and their actions and land can help us learn more about that because it tells us more about military service.

Nicole (5m 57s):

It tells us about when moved into Texas, how long they lived on the land and all kinds of little details, even about their family. Like we talked about last episode. So the land records can, you know, reveal military service if the ancestor or his heirs received a grant for his involvement in the conflict. And these grants include all kinds of things, the surveys maps showing neighbors, and because ancestors could choose their own land, these neighbors were likely family, friends, and acquaintances. When you researched the land grants check also the land grants of neighbors and see if your ancestors mentioned in someone else’s records and did they serve in the military together?

Nicole (6m 38s):

Did they move to the area together? There’s a lot of possibilities for land grant research. So today we’re going to focus on the Republic of Texas and then the state of Texas and how they issued land to all the settlers that came in after independence from Mexico in 1836.

Diana (6m 57s):

Right? So let’s start with the Republic, just a little bit of history on the land, kind of going back to the Mexican Era, the Mexican Congress passed sofa April 6th, 1830. And that is when they prohibited further immigration from the U S they canceled all the impresario contracts that we talked about in the last episode, only let the Austin into wit colonies continue. So of course, this made everyone upset who wanted their family members and friends to join them in Texas. And there was the problem of land speculation. So by 1835, they began this talk of gaining independence from Mexico and delegates from various parts of Texas gathered to draft declaration of independence and the constitution patterned after our guess what that of the United States and Texas the Republic of Texas to credit sovereignty on March 2nd, 1836, and continued as an independent body for almost 10 years until 19th of February, 1846.

Diana (8m 4s):

And that’s when it joined the United States. So we have this period from 1836 to 1846 when we have the Republic of Texas as its own sovereign nation. So once Texas gained independence from Mexico, that first Congress defined the boundaries of the Republic. And then they wanted everyone to bring in their land transactions to the general land office, which they had just formed. They of course, wanted to honor all the previous land grants that have been given by Spain and Mexico and needed those all recorded, which is great for us as researchers, because those are recorded and now digitized and available to us.

Diana (8m 46s):

And then of course, with Texas being such a huge state, there was a lot of vacant land. And that land became the property of the Republic that the Republic could then grant and raise money. So they also needed to fund a militia because they are out here with native Americans, especially on the frontier areas. And then they still have Mexico to the south that is really not happy. And so they want to have a militia to defend against insurrections there. And you know, of course their public isn’t having any money. So they’ve got land and that’s the primary resource much like the United States, you know, as a fledgling country had all this land and no money.

Diana (9m 32s):

So they issued bounty grants to soldiers to try to build up this militia and they would give them land instead of money. And those bounty grants were about, you know, they were based on how long they had served in the army of the Republic. And the Congress continued to pass act after act. And those determine how much land was awarded because this land was so important for revenue. The Republic took great care to obtain the records and they had to gather those and from the land offices that were under the Mexican jurisdiction.

Diana (10m 13s):

So they gathered those in, and then they kept the records as part of the records of the Republic, which later became the state of Texas. So a great boom to researchers that those records are available. So because they are it behooves us to really learn about the records and how they were granted and some of the acts, the laws that they were granted under, because those can tell us so much about our ancestors.

Nicole (10m 43s):

Yes. So let’s start with the land application process. So right after the revolution, it was kind of an unstable period and they were developing, you know, a new government. So during that time, the Republic issued headright grants, and this was from 1836 to 1842, and they did this to keep settlers in Texas. They didn’t want people to fly away. So these grants initially were for 4,605 acres per family, or 1,476 acres per single man. They were really trying to encourage more settlers because the Republic of Texas, they wanted to increase the tax base and they wanted to raise land values.

Nicole (11m 25s):

And also they needed soldiers to protect against Mexican and Native American raids. So their goals were to keep everybody staying in Texas and become stronger. And so in 1837, each county was asked to create a board of land commissioners in order to review all these land claims for headrights. And as you might imagine, because it was kind of unstable at this time period, there were some fraudulent practices that were occurring within the system. Sometimes there were witnesses that were not really credible, but the county boards ended up approving almost all of the claims possibly. This is because the men that were serving on the county boards would have been the friends and neighbors of those applying.

Nicole (12m 8s):

So maybe a little bit of helping each other out in total, over 30 million acres were granted through the system of headright certificates. And so there were several different steps that the applicant needed to go through in order to receive the grant. Then once the steps were completed, the land commissioners approved the patent and the original was sent to the grantee. And then a copy was made for the general land office of Texas. So the sequence of the application was first that you have to complete an application and send that into the board of land commissioners for the county, and then choose land within the county or any county with available land and then marital status.

Nicole (12m 54s):

And your residents had to be proved by two witnesses, and then they had to pay a fee of $5 for a certificate. And then if all this was valid up to that point, you could choose a plot and have it surveyed. And then next was to have the field notes certified and send them with the application onto the land office. And the last thing was to receive a patent signed by the president of the Republic and the land commissioner.

Diana (13m 21s):

So when you get, when you look at the digitized application, you can see a lot of those pieces. For instance, you’ll often see the survey where they detail out specifics about the location, and they’ll draw a little picture on it. Then, then you might see the application with all different things filled in. I’ve looked at a lot of these grants and, and some of them are more complete than others, as you can imagine, but you do sort of see the sequence. So it’s just good to know how it happened. So these headrights are filed under different classes. And if you know the class on your ancestors land grant, then you can learn so much about when they arrived and what your ancestor had to do to receive the headright grant.

Diana (14m 11s):

And so the grants have sort of a cover page and it will say class one, class two, my ancestor so far, all the ones I found say class three or class four, because they came a little bit later, but you’ll see that right on the front of the packet. So let’s start with class one. These are settlers who arrived prior to March 2nd, 1836. And they had not received a Mexican land grant. So they are basically coming in under the first act of the Republic. And so ahead of family could have one league and one labor of land, single man, a third of a league, and you had a previous Mexican grant.

Diana (14m 54s):

You could augment the land up to the allowed amount and you weren’t required to live on the land. So if you have an ancestor under that one, that might explain some things, if you have the living in one place and the land in another place.

Nicole (15m 7s):

Yes. And that happened quite a bit and it can be confusing.

Diana (15m 12s):

Right, right. So that’s why it’s so good to know these requirements. Also, if you have an ancestor, they got married right before that, maybe that, so they could get more land because if they had a family, they got a lot more.

Nicole (15m 25s):

Right. I was just thinking about why, why was that? You know, and I think it just goes back to the reasons of the Republic, trying to build up a, a strong colony or a, you know, a strong nation now with trying to get families, instead of just single men coming in, who maybe were transitory or whatever. Right.

Diana (15m 44s):

And if you have a family you’re probably going to have more stable communities. Yes. People will settled down and, and so that they were, they recognize that. And were trying to incentivize that. So then they pass another act on December, 1837 and called this class two. And so this was for all the people that arrived from 22 March 1836 to 1 October 1837. So a period of about a year and a half, and now they’re knocking down the amount of land. So now heads of families were eligible for 1280 acres and single men, 640 acres.

Diana (16m 24s):

And they had a requirement to reside in their public for three years. So they were trying to get people to come in and get the land and stay put because the 1830s, you know, you’re the other people that are at, this is the frontier and you’re going to have problems and challenges. So not easy. It wants you to stay put then in 1838, they changed it again called this class three. And these were people that arrived from October 1837 to January of 1840. And again, they took the eligibility of acres down to 640 acres for heads of families and single men 320 acres.

Diana (17m 10s):

So each time we’re seeing the amount of acres you could receive, like by half or more, you know, taken down. And again, they were required to reside in the Republic for three years. And then we have class four, which was the act of 1842. And this was everybody who arrived from January1840 to January of 1842. And it was same as for class three, but they added this little requirement that settlers had to cultivate at least 10 acres. So you had to actually do something with a little bit of the land, and these are all filed under the class three heading. So that makes it a little tricky.

Diana (17m 50s):

You know, your ancestor maybe came in during that time period, but it’s under underclass three. So, you know, you just have to be aware of that and then it will make sense. Huh?

Nicole (18m 1s):

That’s really interesting about how they kept reducing the amount of land and increasing the requirements. So I wonder if that was because they had so many people coming and they were afraid of the land, like getting taken up too fast, maybe.

Diana (18m 14s):

Yeah. That could, that could be, and situations change, you know, that’s how laws get made. They make a law and then they see the result of that or a situation changes. And then they have to change the law that happens all the time

Nicole (18m 28s):

And kind of remind predict, Right? Yes. Even cannot predict. It reminds me of the pension laws for Confederate soldiers after civil war and how those changed quite a bit as well, once they saw their response and kind of what people were doing. And they noticed people were getting pensions in all different states. And they were like, okay, you can’t have a pension here if you’ve already had it in somewhere else. Like your pension is based on your residence, not based on where you serve different.

Diana (18m 55s):

Right. Right. Exactly. Yeah. Good point.

Nicole (18m 59s):

Well, let’s talk about colony grants. So this is from 1841 to 1844. After all these different classes, the Republic of Texas still needed more settlers. So they went back to the old Empresario system used by span New Mexico. So that was interesting. They, the Congress gave the president authority to make contracts with individual empresarios and each contract was unique. If you discover your ancestor was part of, one of these colonies, you’ll want to go find out the specifics of that contract so you can learn about it. But in general, the colonists were to come from outside the Republic.

Nicole (19m 39s):

So the goal is to bring in new people and these grants were filed under the class three heading and included four Empresario colonies established under contracts with the Republic of Texas. And the names were Peters, Fisher and Millers, Casters and Mercers. So there were actually a lot of problems associated with these colonies because Texans with land certificates, from the various land grant acts of the 1830s and 42, they wanted to settle in the land, laid aside for the colonies. So some of the Arias settled foreigners from Europe as well, many Texans thought the foreigners were receiving the best land and Empresario act was repealed in 1844, probably because they were all fighting about it over five and a half million acres of public domain land had been conveyed to settlers through this system.

Nicole (20m 40s):

So the populations really grew substantially. And, you know, we talked about there being 30,000 people there. Well, after all these land grants, there were up to 130,000 people living in Texas now, and land prices had risen just as it was hoped. So it’s interesting to look at that and see, you know, the change of the population and how it worked really well with their goals to get more people.

Diana (21m 13s):

Yeah. And maybe they had not predicted that, but they were, I’m sure they were happy to bring in so many people. So it was fun for me to learn about this because I kept seeing in the records that our ancestors were part of the Mercers colony. So I was really curious about that. And so in the blog post, I wrote about those have a little bit of an example from Benjamin Cox, who I talked about before on the podcast is figuring out the he’s the father of my Rachel. And he received a Mercer colony grant and they filed these as third class rights. So that was another confusing thing that they would file those under the third class heading, but Charles Mercer learning about him I found that he put his colonists on the frontier as the defense against the native American or Mexican Raiders.

Diana (22m 8s):

And that makes sense because my Benjamin Cox came from Arkansas and he became a Texas ranger. And I think he was like in his fifties or sixties when he became a Texas ranger. So yeah, he was, and like many other texts is when I followed his land, he sold his original land and then he relocated. So he didn’t want to stay where he originally got the land and, and moved on. And I see that happening a lot. And so on the, in the blog post, a little image I put on there, you can see the survey map showing his neighbors. So these land grants are so amazing when you find the one for your ancestor so much to learn about from them.

Nicole (22m 51s):

Right. And it’s interesting that you said he’s seen it a lot where the original person who was granted the land doesn’t end up staying there, and it seems like more of an investment or a business opportunity for them to get this land super cheap and then sell it for a profit.

Diana (23m 6s):

Right. And a lot of times you’ll see like ASSG meaning it’s the assignee. So that same idea that it’s transferred to someone else. And it can be for a lot of money. I, I looked at one that was for $800, or it can be one for like a hundred dollars. I’ve seen all different amounts of that little cell going on, depending I guess, on the land and how much somebody wanted to put it to purchase a for,

Nicole (23m 33s):

Right.

Diana (23m 35s):

So in 1845, 20 December, 1845, we have Texas statehood. And by 1845, the Republic had evolved from being a land of very landholders as in the Spanish and Mexican Era to being a land of much smaller parcels. So if we can remember some of those land descriptions back in the Mexican Era, you know, a league in a labor and they’re giving away thousands of acres, like 4,000 acres, while now we’re parceling it down to be much smaller, you know, 640 or 320. And so in this way, the Republic got a lot more families to come in a lot more people.

Diana (24m 17s):

And during the 10 years from, you know, 1836 to 1846, the Republic had distributed 40 million acres of land. And in all the years that Spain and Mexico had been in charge, they’d only distributed 26 million acres. So there was a lot of land that was distributed during the era of the Republic, but even more was to be distributed when Texas became a state. So Texas is one of the states that is a state land state because when it joined the United States of America, it retained its public land. And so it kept the right to distribute the land instead of giving it to the federal government.

Diana (24m 59s):

So we’ve got many, many federal land states, all of your states out west, basically our federal land states. And then the ones along the Eastern seaboard, the original colonies are the state lands are states where they under the colony rules, gave out land and then kept that ability to distribute land as well. So if you’re doing land research, you need to discover who was distributing the land federal government or the state, and the state of Texas kept that ability. And when it became a state, the state constitution recognize the land titles by all the previous administration.

Diana (25m 39s):

So you’d receive land under Spain, Mexico, or the Republic, as long as they were valid, they recognize those titles and kept track of those in the general land office. And then they continue to grant land because they still needed to attract new settlers reward settlers, and of course have more revenue.

Nicole (26m 0s):

So now that Texas is a state, how did people buy land from them? Well, it was through these preemption grants a lot of the time. And so starting in 1845, they passed the first preemption act. And this just meant that anybody who settled on and lived on land and then improved it, then they could purchase the land that they were living on. And they could buy it for 50 cents an acre. After three years of living there, settlers were allowed up to 320 acres of vacant public land. And the state of Texas passed a similar law in 1853, but then in 1854, they passed another act, reducing the amount of land to 160 acres.

Nicole (26m 42s):

And then in 1856, this program closed. But following the civil war, preemption was re-instated until the public domain land had been depleted in 1898. A settler could qualify by living on the land, like I said, for three years and making improvements. So they really wanted to reward people who were going to actually live there and settle and improve the land.

Diana (27m 6s):

And a really interesting thing to do is to go look at the tax records. So we talked a little bit about tax records in the last episode, but when you look at those, you can see what they’re doing with the land. We’ll talk about their livestock or all sorts of different things. You can kind of get an idea of, of what’s happening on that land with your ancestor, both the Republic and the state of Texas, as we’ve mentioned Nita to reward the soldiers, they needed this militia and they needed to be able to pay them and they had no money. So they use land and they followed the example of other countries. We see this in the United States and Spain as well, that awarded bounty grants.

Diana (27m 53s):

And we have a lot of different grants depending on the era. We have one that the Republic started called military headrights. So this is back when they were giving a lot of land, 4,605 acres for a head of a family. And this was if a soldier had served in the army or militia from March to August of 1836. So they’re getting a size about sizable amount of land. And then if you were a soldier and you were providing military service to the Republic before October, 1837, you could get up to 320 acres for every three months of military service and get up to 1,280 acres.

Diana (28m 41s):

And that actually went on until 1888. So you might have an ancestor who applied for a bounty grant for his service in 1837, much, much later. And that would seem so confusing unless you understood the grant and the law behind that. So just know again, if you see these terms to go research and figure out why they’re getting the land, and then there were special grants called donation grants. And this was, if your ancestor was in a specific battle, maybe you’ve got a family story that they were in the Alamo where they were at Goliad. And that was to be a reward for their military service.

Diana (29m 22s):

And usually they would get 640 acres, but they’re called donation grants. So if you see the word donation grant know that that was for something that a specific battle as part of the Texas revolution. And then we have veteran donation grants much later in 1879 to 1887, and are again granted to veterans at the Texas revolution and signers at the Texas declaration of independence. So I, you know, again, I kind of wondered how many were still alive, you know, getting land through that. And they repealed it in 1887 because the land was pretty much all conveyed to the public lands. So that’s just kind of an interesting little time period.

Diana (30m 4s):

You know, they maybe couldn’t predict that there’ll be a lot of people wanting that land and had to repeal it. And then of course, we had the civil war in the midst of all this, and they did Confederate script grants for just a short period of time, 1881 to 83. And this was for soldiers who were Confederate veterans who are permanently disabled and a widow could also receive this. And they had to present to credible witnesses of war service. And they had to show that they possess no more than a thousand dollars in property. So that might be, you know, a really interesting record to find for your ancestor and to learn more about them because those witness statements, whenever somebody has to bring in a witness, those are always really valuable information.

Diana (30m 51s):

Part of the problem was, you know, running out of land was that Texas was very, very good about reserving land for schools. And they reserved half of the public domain for the permanent school fund. And that act required that for each certificate, an equal amount of land had to be surveyed for schools. And so that the public kind eventually ran out and they repealed that Confederate script grant. When you look at the, like, if you’re doing a search for your ancestor in the index for the general land office, you will see a lot of these school certificates. And so it’s always really interesting to keep in mind that all this land was reserved for schools.

Nicole (31m 35s):

I saw that on the land grant that you had in the blog post for a Benjamin Cox, that two of his neighbors were school land.

Diana (31m 44s):

Right. Right. And that’s why until I did this research, I didn’t realize there was so much of this school land out there, but it’s a wonderful thing. You just don’t see that in other states quite as much, it’s just different.

Nicole (31m 57s):

Yeah. It’s great that the schools now in Texas have so much space for their football fields and playing lots of sports. No, just kidding.

Diana (32m 9s):

Well, they have a lot of universities there’s, there are a lot of schools there and how neat that there Congress recognized the importance of education in that time period. That’s great.

Nicole (32m 20s):

Yeah. That is really great. Actually, let’s talk now about the Texas Land survey system. So like you mentioned, Texas was not a federal land state, so they didn’t use the federal land survey system of section township and range. Instead they use the unique system, often measured in Spanish units. So the Spanish units we’ve talked about before are the Vara, which is a unit of length and it is Spanish for rod or pole and it measures roughly a yard or a 33 and a third inches. And then we’ve talked about a labor of land. A labor is a measurement of area and is used to equal 1 million square Varas.

Nicole (33m 4s):

And that’s about 177 acres. A league is also a measurement of area and it equals 25 million square Varas are roughly 4,400 acres. Can you tell us about Hickman Monroe and his land in the Mercer colony?

Diana (33m 23s):

Yes. He was a Mercer colonist. And I had seen that when I first started researching years and years ago, and I had done a little bit of research to learn more about it, but it was still kind of confusing to me. So it was great to study this whole history of the land and try to figure out what was going on with him. But in the survey, I kept seeing this little V S and it was all through the records. And then when I finally learned about it, actually I think it’s V R S you know, it’s handwritten. So it’s kind of hard to see all the abbreviations, but then I figured out it’s for a Varas. And so if you see that V S, V R S depending on the handwriting, what it looks like, just know that that’s the unit of measurement.

Diana (34m 9s):

It’s always fun to look at the original, but sometimes it can seem like a foreign language, even if it’s an English that you don’t understand the abbreviations.

Nicole (34m 20s):

And I still don’t even know if I’m saying it right. Is it Varrows or Varas? I don’t know.

Diana (34m 24s):

I don’t know either.

Nicole (34m 26s):

So going back to how these all were organized, the original land grant files are organized by land district instead of county, because after Texas got independence from Mexico and they created the general land office, they started to issue new land patents and validate titles issued under Spain and Mexican role. So when the Republic of Texas was formed in 1836, these original 23 counties didn’t really have well-defined boundaries. And as the population grew, those county boundaries continued to change. So when Texas became a state, the legislature decided to declare that the 36 counties in existence on 15, February, 1846 would become the land districts of the state of Texas.

Nicole (35m 9s):

And so they organized those land grants that were before statehood by land district. And you can see a full color land district map at the Texas General Land Office Website. And it includes three letter abbreviations used for the index, so that you can figure out everything you need to know.

Diana (35m 30s):

It’s really, really helpful to view that map, because these are names of counties that are currently counties. So for instance, a lot of our ancestors, Nicole have grants that are Robertson, but they’re not living in Robertson. And the grant is at a completely different county. And so I was so confused at first about why it would be Robertson, where the actual grant was for like Parker county. But when you look at the map, then you can see that Robertson takes in this whole big swath of about 10 counties. So it just helps you to understand, again, it’s a little crazy and, and can be confusing, but the more you understand about how the land evolves, the more sense you can make of your ancestors record.

Nicole (36m 18s):

Right? That’s so interesting because you just think like the place they lived was kind of static when you read it on a paper, but then when you see the image of all of the counties that were formed from that land district, after the boundaries changed and populations grew, it really puts it into perspective.

Diana (36m 37s):

Yeah. It helps understand things a lot, and it helps you to make new discoveries because you can realize where your ancestor may be was, you know, if you’re seeing a land grant and it was issued in the Robertson land district, our land office, maybe you’re searching Robertson county for all the records and reality, didn’t read carefully and see that the ancestor was really granted land in a whole different county. And that’s where you need to look for records can pay attention. So we’ve talked a lot about the Texas General Land Office, but that is a place that you go to start your search. And the land grant database currently has over 80 to a hundred thousand records.

Diana (37m 17s):

It’s fabulous. So I’m going to tell you a couple of different ways to navigate that. You can start with the Surname Index, which I personally like to do that. And it’s under history. When you go to the basic website, you, you want to look under history and you can see the Surname Index. And the reason I like that is because you have to use the correct spelling when you’re searching for land grants. And we all know that our ancestors used crazy spellings, or they might’ve been indexed strangely, but usually I’ve found the indexes is pretty correct. And it’s just how the ancestor spelled the name or whoever was writing it down, spelled it, that’s all you can go to the Surname Index, and then you can see all the different ways the name could have been spelled.

Diana (38m 4s):

So for instance, for my Shults Surname, my family changed the new spelling from the traditional German spelling in the 1800s. So instead of S C H U L T Z, they changed it to S H U L T S but still, of course, people still spell it with alternate spelling. So in the Surname Index, I can go there and I can find all the instances of different spellings for who I believe are my ancestors, and then make sure I’m getting all their grants when I go to the land ground search. So I usually just start with the Surname Index and, you know, either write down or do a screenshot of it to make sure I’m pulling up all the possibilities in the land grant search, but you could just start at the land grant search as well.

Diana (38m 49s):

And they do on the website, give you some hints, like last name, comma, first name, you know, make sure you’re following the rules. And then it will pull up the different hits. You can click on it. You can click straight into the PDF and view it. There are a few instances where I record is not yet digitized. And so then you could request it from the physical location, but most of the ones that I have looked for have been available now, there are some other websites that can be used. You put in your research plan, the family search catalog, you can search fight Texas Land Grants and do that as a keyword search, or maybe your specific county and Texas Land.

Diana (39m 35s):

So you can play around with the catalog on family search and get some other records. A lot of indexes have been created for specific counties, and maybe those would be helpful to you. And also ancestry.com has a collection called Texas Land Title Abstracts 1700 to 2008, and that is abstracts of original land titles. So if you find your ancestor there, maybe you’ve attached to a record that’s from that collection. Make sure you use that to go to the land grant database at the Texas General Land Office. So you can actually see the original record because it will be so much better now after your ancestor gets the original land grant, then further land transactions took place at the county courthouse.

Diana (40m 26s):

This is just like all the other land research we do. And so you will look for those deeds or other land transactions at the county courthouse and family search has digitized many of these. So I just go to the county and type in the name of the county, and then under land and property and the catalog, you can generally find the category for deeds. Often the county will have a deed index that they digitize. You can find your ancestor there. So there’s so much to be done with land. So fun to really do a study of the land for your ancestor, and especially in Texas, where land was so important.

Nicole (41m 6s):

Yes, it’s really clear how the land grant process was key in building up the population of Texas. So now that we’ve talked about all of that, how can we use land records as evidence in our genealogy research? So we’ve, there’s a lot of details that are included in land records that could provide evidence that can help you link people together. As you’re putting evidence together into a body of evidence, you know, you have your place of immigration where they came from. Sometimes it will say the date of arrival in Texas, evidence of a wife and children, current residents, neighbors, and associates, and even military service.

Nicole (41m 47s):

So it is a good idea to take some time and transcribe the entire land file. We have a blog post with some suggestions for that. Then also you’ll want to use your land records in conjunction with census records and tax court and other records. This will help you kind of get a more complete picture of the ancestors life. And one thing we like to do is create a timeline of their life events and records to kind of see where they lived and what they were doing in a timeline and understand if you have the right information, or if you have maybe two men at the same name and that kind of thing, you can also study the laws and acts that resulted in the ancestor, receiving their land and understand the requirements for those that you can get an idea of what they had to do.

Nicole (42m 34s):

Of course, don’t forget to take advantage of historic maps to help you understand and visualize the lay of the land. The Texas General Land Office has a great land Lease Mapping Viewer. So you can view original Texas land survey boundaries and more

Diana (42m 48s):

Right. It’s really fun to learn about that. And I actually learned about the land and lease viewer map through my Institute that I did last summer. I did the Texas Institute and we explored that great part of the website. So I used my Hickman Monroe Shults’s land patent and plug that in, in the appropriate place. And then I was able to get so many fun maps. So I found it just automatically showed me where one of his land grants was over a current map. And I also saw it in Google maps and about five different varieties. It seems like of maps.

Diana (43m 29s):

And it was really fun because I really had no idea where those land originally was. And when it put it over the current map, I could see it was right off of a main highway. And it was a little bit Southwest of Dallas. It was right by the course of economy, municipal airport. So I was like, wow, I could actually go find this land based on what this website gives me. So that was pretty fun.

Nicole (43m 54s):

Yeah, no, I want to look on Google maps and see how far of a drive it would be to get to the Corsicana municipal airport from Tucson.

Diana (44m 4s):

It

Nicole (44m 4s):

Is great overlay that on today’s map and just kind of see, oh

Diana (44m 9s):

Yeah. I mean, it’s really awesome. And I think part of the reason they did it, and I think the committee or the people that did it because the original surveys are sort of like meets and bounds, you know, it’s go this many Varas to the big Oak tree and then go twenty-five degrees south to this person’s land. I mean, it would be really difficult to figure out the boundaries of your ancestors land based on the survey. So having this available on the website is fabulous.

Nicole (44m 44s):

Really cool. So it is 14 hours from here.

Diana (44m 47s):

Well that you could drive to your ancestors land. How cool would that be?

Nicole (44m 51s):

Yeah, I mean, we’re not too far from the Western edge of Texas, but this is way over near Dallas. So it’s a little further,

Diana (44m 60s):

Well, we have ancestors over in the Western part too. How far to Lubbock? That might be a quicker trip.

Nicole (45m 6s):

Yeah, that one’s only 10 hours.

Diana (45m 8s):

There you go.

Nicole (45m 8s):

Good idea.

Diana (45m 11s):

Well, I hope everybody’s enjoyed this series on Texas Land records. And even if you don’t have ancestors in Texas, maybe you got some ideas about how to use land in your own research.

Nicole (45m 22s):

All right. Well, good luck everybody. We hope you find some good land records and we’ll talk to you again next week.

Diana (45m 27s):

All right. Bye bye.

Nicole (46m 5s):

Thank you for listening. We hope that something you heard today will help you make progress in your research. If you want to learn more, purchase our books, Research Like a Pro and Research Like a Pro with DNA on Amazon.com and other booksellers. You can also register for our online courses or study groups of the same names. Learn more at FamilyLocket.com/services. To share your progress and ask questions, join our private Facebook group by sending us your book receipt or joining our courses to get updates in your email inbox each Monday, subscribe to our newsletter at FamilyLocket.com/newsletter. Please subscribe, rate and review our podcast. We read each review and are so thankful for them. We hope you’ll start now to Research Like a Pro.

Links

National Genealogical Society Conference 2022 – https://conference.ngsgenealogy.org/ and conference program 2022

Navigating the Unique Texas Land Grant System: Republic and Statehood Era 1836-1898 – https://familylocket.com/navigating-the-unique-texas-land-grant-system-republic-and-statehood-era-1836-1898/

Texas General Land Office Website (GLO) – https://www.glo.texas.gov/

Texas General Land Office Land Grant Search – https://s3.glo.texas.gov/glo/history/archives/land-grants/index.cfm

Surname Index – https://www.glo.texas.gov/history/archives/surname-index/index.html

Texas, Land Title Abstracts, 1700-2008 – Ancestry collection – https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/5112/

4 Tips for Transcribing a Multi-Page Document File in Google Docs – https://familylocket.com/4-tips-for-transcribing-a-multi-page-document-file-in-google-docs/

Land/Lease Mapping Viewer – https://gisweb.glo.texas.gov/glomapjs/index.html

Research Like a Pro with DNA Resources

Research Like a Pro with DNA: A Genealogist’s Guide to Finding and Confirming Ancestors with DNA Evidence book by Diana Elder, Nicole Dyer, and Robin Wirthlin – https://amzn.to/3gn0hKx

Research Like a Pro with DNA eCourse – independent study course – https://familylocket.com/product/research-like-a-pro-with-dna-ecourse/

RLP with DNA Study Group – upcoming group and email notification list – https://familylocket.com/services/research-like-a-pro-with-dna-study-group/

Thank you

Thanks for listening! We hope that you will share your thoughts about our podcast and help us out by doing the following:

Share an honest review on iTunes or Stitcher. You can easily write a review with Stitcher, without creating an account. Just scroll to the bottom of the page and click “write a review.” You simply provide a nickname and an email address that will not be published. We value your feedback and your ratings really help this podcast reach others. If you leave a review, we will read it on the podcast and answer any questions that you bring up in your review. Thank you!

Leave a comment in the comment or question in the comment section below.

Share the episode on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest.

Subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, or your favorite podcast app.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive notifications of new episodes – https://familylocket.com/sign-up/

Check out this list of genealogy podcasts from Feedspot: Top 20 Genealogy Podcasts – https://blog.feedspot.com/genealogy_podcasts/

Leave a Reply

Thanks for the note!