Have you ever encountered a marriage bond in your genealogy research? I have used them quite a bit in my research in the mid-south. Today I’m sharing information about marriage bonds and several examples. One of our podcast listeners submitted a question about bondsmen, asking what it meant for a man to be a bondsman on a marriage bond. I will also attempt to answer that question through this post.

What are Marriage Bonds?

In 1741, “An Act Concerning Marriages” was created in North Carolina by the General Assembly, in order to curtail unlawful marriages. This law required couples desiring to be married obtain a license or publish the banns in church for three Sundays. To obtain a license, the groom was required to post a bond of fifty pounds with the condition “that there is no lawful Cause to obstruct the Marriage for which the License shall be desired.”1 The penal sum on the bond was collected from the groom or bondsman if the marriage was found to be illegal. The bondsman was sometimes called a surety – he shared the groom’s obligation. This money was a protection for the future children of the marriage.2

Marriage bonds were used in North Carolina until 1868.3 For most of this time, they were the only record of marriages, until in 1851. A law that year required justices and ministers to return the licenses with certificates showing they had performed the marriage.4

American colonists brought the practice of marriage bonds with them from England. Dating back to the 14th century, the Church of England allowed couples to marry by license, but most couples married by banns. The public reading of banns in the church was done for three weeks, asking if anyone knew a reason the couple shouldn’t marry. Those seeking privacy for their marriage or wanting to hurry it up could obtain a license instead. But to marry by license, the couple were required to pay a fee and complete a marriage allegation and bond.5

In the American colonies, parish churches were not readily available. Before parish churches were set up and available to publish banns, many colonies required couples to marry by license. Some bonds remain from the colonial period. Some, like New York’s, were mostly lost. New York Marriage Bonds from 1664 to 1911 were damaged in the fire at the New York State Library, but Kenneth Scott created a book of abstracts of the surviving bonds called New York Marriage Bonds, 1753-1783.6

Colonial Texas required marriage bonds under Spanish law.7 Databases for colonial marriage bonds and other ways to find colonial marriage bonds will be discussed later in this post.

Several states continued to use marriage bonds after the colonial period, mostly in the South.

Where were marriage bonds used?

Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee continued the use of marriage bonds for many years after statehood. I have also found marriage bonds in Louisiana in the 1800s.

Other British colonies required marriage bonds at times as well. For example, in Canada, from 1779-1858, to obtain a civil license, the Crown required a bond entered into by the bridegroom with two sureties, if not married by an Anglican or Roman Catholic church clergyman.8

As I searched for collections in the FamilySearch catalog with the words “marriage bonds,” I noticed almost all the U.S. results were from Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, or Tennessee. The rest were from England, Canada, Wales, or Ireland. Some derivatives from other states were labeled marriage bonds, but were actually just licenses. Where have you seen marriage bonds in your research? Please share in the comments.

Marriage bonds were usually filed with the bride’s county of residence. The marriage usually took place a day or a few days after the date on the bond. The certificate was not always returned after the marriage. Just because you find a marriage bond, it doesn’t necessarily mean the marriage took place.

Colonial Marriage Bonds Examples

I browsed through some colonial marriage bonds to find some examples. Here is one from North Carolina, and then one from Pennsylvania.

I browsed through some colonial marriage bonds to find some examples. Here is one from North Carolina, and then one from Pennsylvania.

John Dwyer, North Carolina, 1756

John Dwyer and Jacob Blount bound themselves to pay fifty pounds to “our Sovering Lord King George the second his Heirs and Successors” on 29 May 1756, in a marriage bond. The obligation stated, “The conditions of this obligation that whereas a marriage is intended between John Dwyer and Jemina Long both of this county of Tyrrell aforesaid, Virgin woman, Now if there is no lawfull cause to obstruct the said marriage, then the above obligation to be void…”9

Joshua Farrell, Pennsylvania, 1785

In 1785, Thomas Harrison, Currier, and Joshua Farrell, Mariner, of the City of Philadelphia, entered into a bond due to the upcoming marriage of Joshua Farrell and Mary Anne McCartney.10 Although this record is technically toward the end of the Revolutionary War, it’s still a pretty good example of the colonial era bonds.

In 1785, Thomas Harrison, Currier, and Joshua Farrell, Mariner, of the City of Philadelphia, entered into a bond due to the upcoming marriage of Joshua Farrell and Mary Anne McCartney.10 Although this record is technically toward the end of the Revolutionary War, it’s still a pretty good example of the colonial era bonds.

The bond obligation was interesting. It stated:

“The condition of the obligation is such, that if there shall not hereafter appear any lawful let or impediment, by reason of any Pre-contract, Consanguinity, Affinity, or any other just Cause whatsoever, but that the above-mentioned Joshua Farrell and Mary Anne McCartney, may lawfully Marry; and that there is not any Suit depending before any judge, for or concerning any such Pre-contract; and also if the said Parties, and each of them, are of the full Age of Twenty one Years, and are not under the Tuition of his or her Parents, or have the full Consent of his or her Parents or Guardians respectively to the said Marriage; and if they, or either of them, are not indented Servants, and do and shall save harmless and keep indemnified the above-mentioned John Dickinson Esquire…and shall likewise save harmless and keep indemnified the Clergyman, Minister, or Person who shall join the said Parties in Matrimony, for, or by Reason of his so doing; then this Obligation to be Void and of none Effect, or else to stand in full Force and Virtue.”

Marriage Bonds Examples from the United States

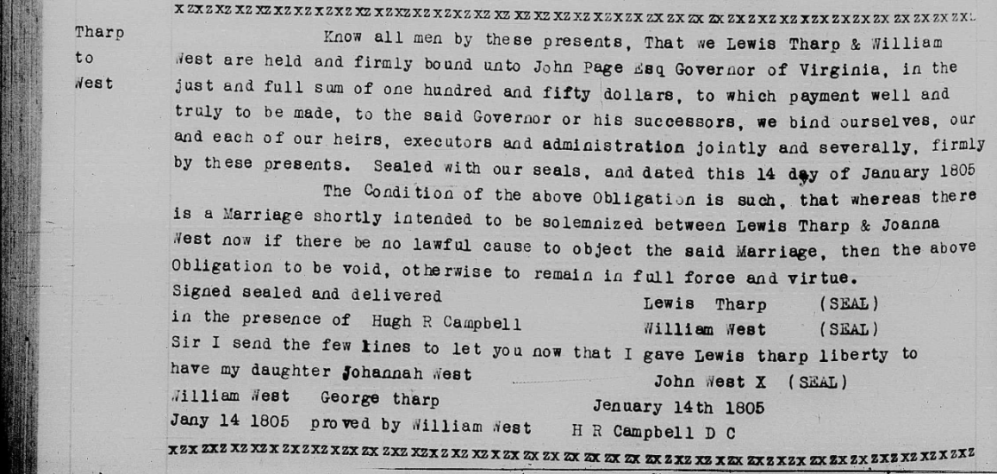

In my research, I have come across several marriage bonds for my ancestors and research subjects. One, for example, is the marriage of my husband’s 4th-great-grandparents, Lewis Tharp and Joanna West.

Lewis Tharp and Joanna West, Virginia, 1805

Lewis Tharp and Joanna West were married in Fauquier County, Virginia in 1805. The only record that remains of their marriage is the bond, which includes the consent of Joanna’s father. Since she was not yet twenty-one, her father, John West, provided his written permission. The bondsman was William West, who was almost certainly the brother of Joanna West.11

George Tharp and Polly Noland, Virginia, 1801

Another bond I came across when researching the West family is the marriage bond of George Tharp and Polly Noland. The bond is dated 12 January 1801 in Fauquier County. John West was the bondsman.12

I determined there were two connections between George Tharp and his bondsman, John West. First, John West was the uncle of Polly Noland. Polly’s mother, “Gemime Noland,” provided her permission for Polly to marry George Tharp, because she was not yet age 21. Jemima (Arnold) Noland was the sister of Bathsehba Arnold, who was the wife of John West. Jemima was widowed by the time Polly was married, which is probably why uncle John West was asked to be the bondsman.

The second connection between John West and George Tharp is that John West paid taxes for George Tharp in 1799 and 1800.13 This could indicate that George Tharp was employed by John West, perhaps as an apprentice or servant. Men who employed others were usually responsible for paying the taxes of those servants or apprentices.14

John West and Sally Webb, Virginia, 1805

John West entered into a marriage bond on 5 June 1805 in Fauquier County, Virginia, with the intent to marry Sally Webb. The bondsman was Richard Webb, likely Sally’s brother.15

In my current research project, I’m looking for clues about John West’s origins. I noticed that the witness to the marriage bond was Daniel Withers. I had seen a marriage between a Sally Withers and Charles West, and thought maybe the Withers connection was showing that our John West could be related to Charles West. However, I checked to see if Daniel Withers was a witness on other bonds, and sure enough, he witnessed several other bonds in Fauquier County in that same time period, and he was a clerk of the county court. I later learned that the witness on marriage bonds was often the clerk.16

Mary Johnson and Benjamin Davis, North Carolina, 1800

Several years ago, I worked on a project to discover the origins of John Johnson of Rowan County, North Carolina. Here is an excerpt from the report:

Mary/Polly Davis and her husband Benjamin Davis were petitioners in the probate file of John Johnson in 1825. In their petition, they stated that they were married in Rowan County.17 Marriage records were searched, and a bond was located for Benjamin Davis and Mary Johnston, dated 24 Oct 1800, with Randolph Johnston bondsman.18

Finding out that Randolph Johnson was the bondsman was a significant finding. It helped cement the fact that the Mary Johnson, wife of Benjamin Davis, was the sister of Randolph Johnson and the daughter of John Johnson.

John Beasley and Sina Doherty, Kentucky, 1808

In this example, I was trying to find a connection between a cluster of DNA matches and my husband’s third-great-grandfather, John Robert Dyer. The common ancestors of the cluster were a group of Daughertys and Taylors who migrated from Craven County, North Carolina to Warren County, Kentucky. I found several matches descending from Robert Daugherty and Sarah Taylor, so I worked on finding all of their children. In that process, I found a marriage bond for one of their daughters, Sina Daugherty. She married John Beasly in 1808. Robert Daugherty was the bondsman, almost certainly Sina’s father.19

To understand the marriage bonds I was finding for the Daugherty children in Warren and Butler Counties, I did some research into the laws of Kentucky. I found this in the Statute Law of Kentucky:

“every license for marriage shall be issued by the clerk of the court to that county wherein the feme usually resides in the manner following, that is to say: the clerk shall take bond with good surety for the sum of fifty pounds current money, payable to the governor for the time being, and his successors, for the use of the commonwealth, with condition that there is no lawful cause to obstruct the marriage, for which the license shall be desired; and every clerk failing herein, shall forfeit and pay fifty pounds current money: and if either of the parties intending to marry, shall be under the age of twenty-one years, and not theretofore married, the consent of the father or guardian of such infant, shall be personally given before the said clerk, or certified under the hand and seal of such father or guardian, attested by two witnesses, and thereupon the clerk shall issue a license, and certify that bond is given; and if the parties, or either of them, be under the age aforesaid, he shall also certify the consent of the father or guardian, and the manner thereof, to any minister legally authorized to celebrate the rites of matrimony; and every license so obtained and signed, and no other whatsoever, is hereby declared to be a lawful license…”20

Augustus Dyer and Lucinda Woods, Tennessee, 1849

Augustus Dyer entered into a bond to marry Lucinda Wood in Hawkins County on 7 November 1849. The bondsman was William Tharp.21 The connection between Augustus Dyer and the bondsman was not through the bride. This time, the bondsman was an associate of the groom. Augustus’s mother was Barsheba (Tharp) Dyer, so William Tharp was almost certainly the groom’s uncle.

Who were the bondsmen?

Typically, the bondsmen were a relative of the bride: father, brother, etc. In my examples, the bondsmen were the following relatives:

- Bride’s father

- Bride’s uncle and groom’s employer

- Bride’s brother

- Groom’s uncle

- Bride’s brother-in-law

The last bullet in the list is from an example I will share in the next part of this series on marriage records. You’ll see that most of the bondsmen are relatives of the wife. If the surnames of the bride and the bondsman don’t match, you might be looking for an uncle or brother-in-law connection. Another possibility accounting for a different surname is that the woman may have been married before. In that case, the bondsman could also be from her first husband’s family.

After this was published, a reader asked a great question. I thought I would add my response up here. She wondered how old a man had to be in order to be a bondsman. The answer has to do with common law. American colonies followed British common law and continued to do so with some differences into statehood. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_the_United_States#American_common_law for more info. To learn about what common law allowed for infants under age 21, see https://genfiles.com/articles/legal-age/. William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England published 1765-1769 stated that “an infant can neither aliene his lands, nor do any legal act, nor make a deed, nor indeed any manner of contract, that will bind him” (Book the First, p. 454). After that, Blackstone listed some exceptions, but none that allowed a man younger than 21 to be a bondsman. The only contracts an infant could make were binding himself as an apprentice and appointing his guardian. See https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30802/30802-h/30802-h.htm pages 453-454.

How to Find Bonds

FamilySearch Catalog

For North Carolina, use the database index at Ancestry or FamilySearch. The Ancestry database is great because it allows you to search using the bondsman’s name; but it’s not attached to original images. The FamilySearch database will be better for finding the original images.

For Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, type in the county where you think the couple was married into the FamilySearch Catalog place field. Go to the listings for that county and look under vital records for marriage bonds.

For colonial marriage bonds, you can also do a FamilySearch catalog place search. You may also want to check for indexes or images on state archives’ websites.

Books of Local Records Abstracts

Bondsmen aren’t always included in indexed online databases, so it’s harder to find your ancestor as a bondsman for someone else. However, looking in abstracts of marriage record books for the locations your ancestor lived can help you find out if your ancestor served as a bondsman for someone else. To do this, go to the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, or another genealogical library, and find books of abstracts for the county your ancestor lived in. Check the index to see if he or she is mentioned in the book.

Databases with Marriage Bonds

Below are some examples of databases on the web that have marriage bonds.

“North Carolina, U.S., Index to Marriage Bonds, 1741-1868,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/4802/). Description of the database: “When planning to marry, the prospective groom took out a bond from the clerk of the court in the county where the bride had her usual residence as surety that there was no legal obstacle to the proposed marriage. On file in the North Carolina State Archives are 170,000 marriage bonds, covering the years 1741-1868. These records were abstracted by the Works Progress Administration. Most of the bonds contain the following information: groom’s name, bride’s name, date of bond, bondsmen, witnesses. For those with ancestors in early North Carolina, this will be a helpful database. Additional information may include parents’ names, date of the marriage, person performing the ceremony, and other similar data.” This index at Ancestry was originally created by the North Carolina Archives. Read more about their process for creating the index here: North Carolina State Archives, “Overview of the Marriage Bonds filed in the North Carolina State Archives,” revised 2002; image copy, North Carolina Digital Collections (https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p249901coll22/id/641435 : accessed 10 Dec 2022).

New Jersey, “Colonial Marriage Bonds, 1665-1799,” State of New Jersey Department of State (https://wwwnet-dos.state.nj.us/DOS_ArchivesDBPortal/ColonialMarriages.aspx : accessed 10 Dec 2022). A description of the database says, “This database indexes early marriage bonds held at the New Jersey State Archives. During this period prospective marital partners were required to file a bond with the governor. By signing the bond, the partners were swearing they had no preexisting marital contract or other impediment to hinder the marriage. These bonds obligated the groom and his fellow bondsman (often a relative of the bride) monetarily, should the terms of the bond not be fulfilled. In practice, only a minority of marriages were licensed by the colony in this fashion. The database includes 11,533 bonds and 23,066 names. It indexes the names of the bride and the groom, their counties of residence, and the date on which the bond was filed. Note that this is not the date of marriage and in fact could be after a religious ceremony had already been performed. In cases where the bride, groom, or both, were minors, parental consent was required and the parents’ permission is recorded with the bond as well. Such information, however, has not yet been captured in the database. To order a copy, click “Select” next to the record. Selected records are added to the shopping cart at the bottom of the page.”

“Somerset, England, Marriage Registers, Bonds and Allegations, 1754-1914,” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/60858/). Description of the database: “Marriage bonds and allegations were drawn up when an application for a marriage licence was made. When applying for a licence the groom would have to swear that there were no impediments to the marriage. This document was known as a marriage allegation. They usually record names, ages, occupations, residences, condition (eg. Bachelor, spinster) and the proposed location of the wedding. Marriage bonds were sworn statements containing assurances by friends or relatives that there were no reasons why the marriage shouldn’t take place.”

Next Post

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading all about marriage bonds! In the next post, I will share an example of a marriage bond from Louisiana in 1860, and how I researched the bondsman to find out how he was related to the couple. It opened some fascinating research connections! You can read the post here: Identifying a Louisiana Marriage Bondsman.

See the other posts is our marriage records series here:

Back to the Basics with Marriage Records Part 2 : Substitute Marriage Records

Back to the Basics with Marriage Records Part 3: Church Marriage Records

Back to the Basics with Marriage Records Part 4: Civil Marriage Records

Sources

- Helen F. M. Leary, editor, North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History, 2nd edition (Raleigh; North Carolina Genealogical Society: 1996), 152.

- Helen F. M. Leary, editor, North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History, 2nd edition (Raleigh; North Carolina Genealogical Society: 1996), 156.

- Helen F. M. Leary, editor, North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History, 2nd edition (Raleigh; North Carolina Genealogical Society: 1996), 155.

- Helen F. M. Leary, editor, North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History, 2nd edition (Raleigh; North Carolina Genealogical Society: 1996), 158.

- “Marriage Allegations, Bonds, and Licenses in England and Wales,” FamilySearch Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Marriage_Allegations,_Bonds_and_Licences_in_England_and_Wales : last edited on 8 December 2022, at 22:01).

- “Marriage Bonds,” New York State Archives(http://www.archives.nysed.gov/research/res_tips_005_marriagebonds.shtml : accessed 10 Dec 2022).

- Kimberly Powell, “Marriage Records: Types of Marriage Records for Family History Research,” ThoughtCo. (https://www.thoughtco.com/marriage-records-types-4077752 : updated 14 Oct 2019).

- “Marriage Bonds, 1779-1858 – Upper and Lower Canada,” Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/vital-statistics-births-marriages-deaths/marriage-bonds/Pages/marriage-bonds-upper-lower.aspx#d : accessed 10 Dec 2022).

- Tyrell County, North Carolina, Marriage Bonds, John Dwyer-Long, 29 May 1756; image online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-81BY-9PB : accessed 10 Dec 2022).

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, marriage bonds, Joshua Farrell and Mary Anne McCartney, 5 May 1785, Philadelphia; image online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C91S-N9GP-6?i=1236&cc=1589502&cat=685442 : accessed 10 Dec 2022), DGS 7734098, image 1237 of 1337.

- Fauquier County, Virginia, Marriage Bonds and Returns 2:370, Tharp-West marriage bond, 14 Jan 1805; images online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9XF-6BPB : accessed 18 Aug 2020), DGS 7578972, image 451 of 688; FHL microfilm 31633.

- Fauquier County, Virginia, Marriage Bonds and returns 2:227, bond, George Tharp – Polly Noland, 12 January 1801; images online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99XF-6182 : accessed 25 Aug 2020); citing FHL microfilm 31633.

- Fauquier County, Virginia, Personal Property Tax Lists, 1800, P. Charles Pickett District, p. 33, line 10, John West; image online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSQ2-W1MB : accessed 6 October 2022), DGS 7849107, image 267 of 861.

- “Taxes in Colonial Virginia (VA-Notes),” Library of Virginia (https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/va20_coltax.htm : accessed 19 November 2022).

- Fauquier County, Virginia, Marriage Bonds and Returns 2:382, West-Webb marriage bond, 5 June 1805; image online, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89XF-69MC-5 : accessed 15 March 2022), DGS 7578972, image 457 of 688; FHL microfilm # 31633.

- Helen F. M. Leary, editor, North Carolina Research: Genealogy and Local History, 2nd edition (Raleigh; North Carolina Genealogical Society: 1996), 156.

- Davidson County, North Carolina, Estate File for John Johnson, 1825, petition of Benjamin and Polly Davis; image online, North Carolina Estate Files, 1663-1979,” > Davidson County > J > Johnson, John (1825), image 7, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org : accessed 14 Nov 2018); citing FHL microfilm 1888955

- Rowan County, North Carolina, Marriage Bonds, Davis-Johnston, 24 October 1800; image online, “North Carolina Marriage Records, 1741-2011,” image 2981 of 10647, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/7515934:60548 : accessed 19 November 2019); citing North Carolina County Registers of Deeds.

- Warren County, Kentucky, loose papers and miscellaneous records, marriage bond, John Beasly and Sina Doherty, 24 Feb 1808; “Kentucky, County Marriages, 1797-1954,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9BJ-VXLV : accessed 16 Apr 2020) DGS 7724941, image 131 of 653; citing FHL microfilm 164,030.

- William Littell, The statute law of Kentucky; with notes, prælections, and observations on the public acts. Comprehending also, the laws of Virginia and acts of Parliament in force in this commonwealth; the charter of Virginia, the federal and state constitutions, and so much of the King of England’s proclamation in 1763, as relates to the titles to land in Kentucky (Frankfort, KY: William Hunter, 1810) 67; image copy, Google Books, (https://books.google.com : accessed 22 Apr 2020).

- “Tennessee, County Marriages, 1790-1950,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:V5HC-3KK : 22 Aug 2020), marriage bond, Augustus Dyer and Lucinda Woods, 7 Nov 1849, Hawkins, Tennessee; citing Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville.

13 Comments

Leave your reply.