Do you have ancestors who immigrated to the United States since 1790? Have you discovered their village, town, or even country of origin? Family stories or census records might give clues but often give conflicting information. Is there another record type that could give additional hints to your ancestor’s homeland? Naturalization records might provide important details but what are these records, and how do you find them? This three-part series will address those questions and give you a foundation in this sometimes confusing record set.

Why Use Naturalization Records

Many record collections are now easily searched online, and because we use them often, we understand their value. Census records list families and relationships, ages, birthplaces, and more. Vital records provide direct evidence of birth, marriage, and death. Obituaries can name numerous family members. But what can naturalization records provide? Some of the information that could be included: nation of origin, foreign and Americanized names, residence, and date of arrival.

When our ancestors arrived in the United States, they likely wanted to become United States citizens. Having left their homelands behind, they embraced their new country and the right to vote and own land that came with citizenship. Though these records can be more challenging to discover, they add another piece to the puzzle of our ancestor’s lives. A naturalization record before 1906 may not reveal a specific village, but it will name the home country of your ancestor. Because this era of record keeping was not standardized, it’s always possible that additional information about the ancestor’s homeland was also included. Could a helpful clerk have written in additional facts? Without searching for the records, you’ll never know.

The Naturalization Process

Your ancestor had to go through a multi-step process to become a United States citizen. In your census research, you may have noticed the initials AL, PA, NA, or NR written in the column of “Citizenship.” AL signified an “alien” or non-citizen. PA meant a Declaration of Intent had been filed, sometimes called First Papers. NA denoted a naturalized citizen. NR stood for Not Reported. Different census years reported various information on citizenship, with some years reporting none. See the end of this article for a list of U.S. Federal Census records with citizenship information.

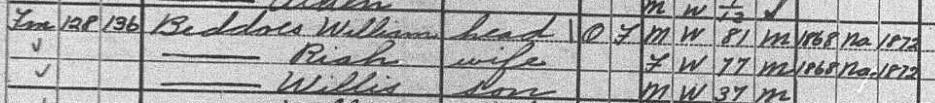

My maternal ancestors immigrated in the mid 1800s, so there could possibly be naturalization records. Viewing the 1900 census for my 2nd great-grandfather, William Beddoes, I saw the following information in the “Citizenship” category on the far right of the census line.

-Year of immigration to the United States: 1868

-Number of years in the United States: 32

-Citizenship: NA or naturalized

1900 census for William Beddoes, Salem, Utah County, Utah

Armed with the knowledge that William was naturalized between his arrival of 1868 and the 1900 census, I could then search for a naturalization record. Many people sought citizenship within five years of their arrival so they could vote and own land – depending on the laws of the state and time.

William would have gone through the following steps before becoming a citizen:

– Filed his Declaration of Intention or First Papers.

-Met the residency requirement, usually five years.

-Submitted a Petition for Naturalization, also known as Second or Final Papers.

-Taken an oath of allegiance or naturalization oath, which may be filed with the other documents.

-Received a certificate of naturalization.

Locating a Naturalization Record

If your ancestor was listed in the 1920 census, the year of naturalization was included in the Citizenship section. Viewing this census for William Beddoes, I discovered the year 1872 written in both William’s line and that of his wife, Riah. Did she also have to go through the naturalization process? No, during this time period, a woman automatically became a United States citizen through her husband. William’s children under 16 also automatically became citizens with his citizenship. Because the naturalization laws changed throughout history, always consult the law at the time your ancestor would have been seeking naturalization.

1920 Census, Salem, Utah County, Utah, William Beddoes household

Narrowing the search to a specific time frame is important because these proceedings may have gone through a federal, state, or local court as long as it had the authority to grant citizenship. Each locality has its own court system, so you may see terms such as superior or common pleas courts on the county level. A state, U.S. circuit court could have been used as well as a district court. Other courts on the local level could be municipal, police, criminal, or probate.

Another consideration when searching for your ancestor’s naturalization record is the possibility that he filed his first papers in one court, then moved on and completed the petition for naturalization in another location. Tracking your ancestor in all available records for his life will give you clues to narrow the search.

In the case of William Beddoes, he stated a naturalization year of 1872, so the 1870 census would be the best indication of his locality in 1872. That census reveals his residence in Pondtowne, Utah County, Utah. The 1870 census included a final column titled “Constitutional Relations” and asked if a person was a “Male Citizen of U.S. of 21 years of age and upward.” As would be expected, William’s line does not have a tick mark like other men on the page because he had not yet been granted citizenship.

Searching the Records

My go-to place to discover records is the FamilySearch Catalog. Because Williams’s 1870 residence was in Utah County, Utah, I started with that location and clicked on the Naturalization Records category. The image below shows the record collections available. Starting with the most likely collection, I selected Utah, Utah County, Naturalization Records, 1859-1927. Notice this contained the records of two different courts: those for Utah County and Utah Territory. Statehood didn’t occur until 1896, so William would have used territorial courts. As part of our locality research, we can learn about the court system used in the time and place of our ancestors to understand the records.

https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog > Place search “United States, Utah, Utah” > Naturalization and Citizenship

Selecting the Utah, Utah County, Naturalization Records collection highlighted above brought me to the page detailing those records. I saw that I could view digital images of these records and that they were not available on microfilm, an example of the many records that FamilySearch is digitizing straight from the originals.

When I clicked “here,” I was taken to a page with fields for searching for my ancestor. Entering in the name “William Beddoes” brought no results. Did this mean his record was not in the collection? Not necessarily. It just might not have been indexed yet. In this scenario, I prefer to use the browse feature and search myself. The following path led me to the actual digitized record: Browse through 105,474 images > Naturalization records > Declarations of intention, 1871-1875.

“Utah, Utah County Records, 1850-1962,” Naturalization records > Declarations of intention, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99KY-XWNF? : accessed 3 April 2020); film #100585103, image 1; citing Utah County Records Center Spanish Fork.

Whenever I begin viewing a collection, I look to see if the volume is indexed, and in this case, it was. Guess who appeared on the “B” page? William Beddoes. The number 9 after his name indicated his record on page 9. Moving forward a few pages located his Declaration of Intention to become a citizen of the United States of America. Because he was English, he renounced his sovereignty to Queen Victoria. Unfortunately, we don’t know if he really was from England based on this record – he could have been Scottish, Welsh, or Irish. But we do know that William went to the court and started the naturalization process on 28 June 1873. Combined with census records stating his country of origin as England, this adds another piece of evidence to his origins.

Did you notice the conflicting dates? William stated on the 1920 census that he was naturalized in 1872, yet this document clearly states that he began the process in 1873. Both are original sources, but the one created at the time of the event would provide more accurate information than that reported almost fifty years later. By carefully seeking out each record for our ancestors, we can compile a more accurate view of their lives.

“Utah, Utah County Records, 1850-1962,” Naturalization records > Declarations of intention, 1871-8175, for William Beddoes, 1873, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99KY-XWX5? : accessed 3 April 2020); film #100585103, image 31; citing Utah County Records Center Spanish Fork.

The next step for William was to meet the residency requirement and then submit his petition for final papers. My next step is to search additional records to discover William’s petition for naturalization and his oath of citizenship.

William Beddoes and Mariah Brockhouse Beddoes

Tips for Naturalization Research

-Start with a survey of known records for your ancestors to determine when they might have immigrated to the United States

-Look at census records, military papers, voting registers, passports, and homestead records for clues to a specific time frame and location where your ancestor might have begun the process.

-Realize that your ancestor might have begun the process and filed a declaration of intention even if he didn’t complete the process.

-Use the FamilySearch Catalog to find the naturalization records for the time and place.

-Search the records using the indexed records first and then the browse feature.

-Track the searches in a research log.

-If there are no results, expand the search to other nearby courts, or other time frames.

U.S. Federal Census Records Reporting Citizenship

-1820: Number of foreigners not naturalized

-1830: Number of white aliens / foreigners not naturalized

-1870: Male citizens 21 and over, and number of such

-1900: Year of immigration to the US; number of years in the US whether still an alien, having applied for citizenship, or naturalized ( AL=Alien, PA=First Papers Filed, NA=Naturalized)

-1910: For foreign-born males 21 years old or older: whether naturalized or alien (AL=Alien, PA=First Papers Filed; NA=Naturalized)

-1920: Whether naturalized or alien (A or AL=Alien; NA=Naturalized; NR=Not Reported; PA=First Papers Filed), and year of naturalization – only census to do so

-1930: Year of immigration, whether naturalized (Na=Naturalized, Pa=First Papers, Al=Alien)

-1940: Birthplace; citizenship if foreign born (Na=Naturalized, Pa=Having First Papers, Al=Alien, Am Cit=American Citizen Born Abroad)

Part 2

In the second part of this series, we’ll look at the naturalization laws in more detail.

Part 3

In the third part of this series, we’ll discuss additional places to search and view an example of 20th-century naturalization, so stay tuned.

Best of luck in all your genealogical research!

Save to Pinterest

Leave a Reply

Thanks for the note!