September 2024: The Research Ties program mentioned in this blog post is no longer available.

How do you keep track of the numerous websites, books, microfilms, and other sources you might consult in your genealogy research? Do you only print or save links to the sources you found? What do you do when you don’t find anything in a database? Learning to keep a research log and use source citations is the next step in your journey to research like a pro.

The terms “research logs” and “source citations” might seem overwhelming but you’ll be glad to know that it’s not hard to keep a research log that has good source citations attached. In fact, after disciplining yourself to record your searches you won’t want to go back to your old methods.

This is the fifth in the Research Like a Pro series. So far you’ve learned to create a research objective, analyze what you’ve already found, research the location, and make a research plan. Now you’re ready to start following your research plan and look for records in the sources you identified.

To learn all the steps in the process in one, organized format, you may want to try my book, Research Like a Pro: A Genealogist’s Guide.

Two key elements are at work here – creating a source citation and keeping a research log.

Source Citations

When is the best time to create a source citation? When you’re looking at the source! Don’t fool yourself that you’ll go back and add details like the book title, page number, image number, etc. You’ll be lucky to even find the source again. I’m going to share with you a simple approach that has helped me immensely.

First some definitions are in order.

What is a source? A document, book, article, microfilm, photograph, website, etc. that gives you information, which becomes evidence in proving a conclusion.

What is a source citation? A statement identifying the specific location of a source and details about that source.

Tom Jones, in Mastering Genealogical Proof, explains that a source citation can be created by answering five questions. I wrote about his “who, what, when, where within, and where in method” of creating a source citation in my article, “Source Citations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” You’ll want to review that post for more details and examples. In a nutshell, if you answer five questions, your source citation will lead you back to the original source. It will also help other researchers follow your path. The five questions:

1. Who created the source -often a government or religious entity, an author, etc.

2. What is the source – the 1830 census, a marriage record, a letter, etc.

3. When was the source created or when did the event occur – be specific, month, day, and year.

4. Where within is the source located – a page number, image number, etc.

5. Where in the world is the source – the publisher’s location, the URL, or location of the document if unpublished.

For example, below is the photocopy of my great grandparent’s marriage license and certificate inherited from my Dad’s research. The license and certificate are the source holding information on their names, residence, and date and place of marriage. I used that information as evidence to prove their marriage as well as their residence in Indian Territory in 1898. Below the image is the source citation answering the five questions above.

Carter County, Oklahoma, photocopy of original marriage license and certificate, unpaginated, Shults-Rayston, 11 December 1898, Indian Territory Southern District, recorded 1943, County Court Clerk, Ardmore, Oklahoma.

Where do you create and record your source citation? On your research log! Once you have it saved there, you can use it anywhere that you share the source. I used the above citation in several places: adding the marriage license and certificate to my Ancestral Quest database, uploading the document as a source on FamilySearch and Ancestry, and proving this marriage in my four-generation Royston report for accreditation.

Research Logs

I can tell that a lot of people are interested in research logs. My post “Research Logs: The Key to Organizing Your Family History” has over 12,000 views and continues to get many views every day. Why so popular? Every researcher struggles with keeping organized. Having a method for logging your research helps tremendously .

I’ve discovered that three main types of research logs fulfill my needs as a researcher: a research notebook, an electronic research log, and the web based program, Research Ties.

The Research Notebook

I keep a research notebook with the date, what I hope to accomplish, and what I did accomplish that research session. I use this simple method for working on the collaborative FamilySearch FamilyTree or my Ancestry tree. Because the hints generated by the two websites make research as simple at times as attaching a source, I just record that I “attached a marriage record.” I also note the ID numbers and names of any individuals I want to explore in the future so that when I come back to working on that tree I remember what I was doing. Any records that I attach automatically have a source citation created by the website so no need to write it in my notebook unless there’s a special circumstance I want to record.

The Electronic Research Log

When I’m working on a more involved research project I use an electronic research log. I’ve tried out the table feature of Microsoft Word and Google Docs and that works fine. But I’ve settled on Google Sheets as my preferred method. The ability to easily sort by various columns makes it easy for me to evaluate my findings. Everything I enter is automatically saved and I can refer to past versions if I make a major error. My research log is available on all of my devices through my Google account. I can access my research logs on my phone, laptop or any computer that has internet access.

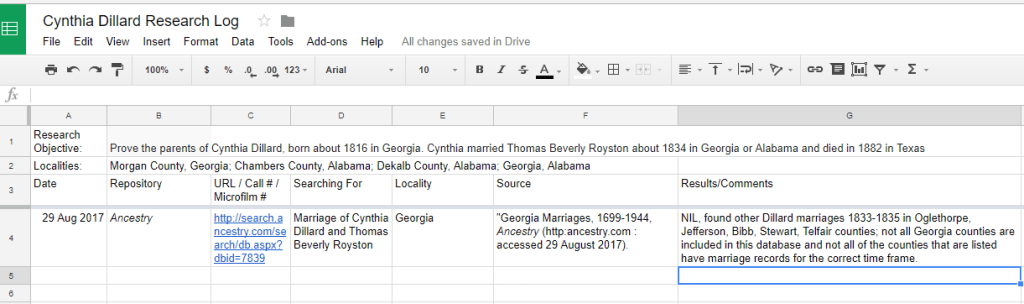

I have created a research log template and whenever I start a new research project I make a copy of my template, rename it, and save it in the file of the individual I’m researching. My research log template has the research objective and localities I’m researching at the top. This helps me stay on track with my research and not head off in another direction. Note the categories I’ve set up: Date, Repository, URL/Call#/Microfilm#, Searching for, Locality, Source, Results/Comments. Those may seem complicated but I’ll show you exactly how and why I use each column.

My research objective is to prove the parents of Cynthia Dillard, born about 1816 in Georgia. My plan includes a search for her marriage record, census, probate, court, and land records for possible fathers in the areas that she lived. First on my list is locating a marriage record for Cynthia and Thomas Beverly Royston. I’ve searched previously for this marriage, but didn’t record my searches, so I’ll do it again. This time the search will be recorded on my research log.

Details from my log:

Date: 29 Aug 2017

Because you’ll be saving this research log and may not return to it for a few months or even years, it is extremely important to note the date you performed the research. Some databases are updated periodically and need to be rechecked at a later date.

Repository: Ancestry

The repository is the website, library, archive, or other physical location that holds the source. It might even be your own files if it is a letter or photocopy you’ve inherited.

URL/Call#/Microfilm# : http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=7839

In this column I copy and paste the URL from the website. Because Ancestry’s URL’s can be really long, I often use the BITLINKS website to create much shorter links for my research logs. If I’m researching at a library or archive, this is where the unique call number or microfilm number goes.

Searching for: Marriage of Cynthia Dillard and Thomas Beverly Royston

This column tells me exactly what I was looking for. With a spread sheet, I can sort all of my marriage searches, or all of the census searches. It helps me organize as I’m researching.

Locality: Georgia

Be specific here. If you’re checking a general statewide index, just the state is fine. But, if you’re looking in a specific county or township, list that.

Source: “Georgia Marriages, 1699-1944,” Ancestry (http:ancestry.com : accessed 29 August 2017).

This is where the source citation goes. Because I didn’t find anything in this database, I don’t have any specifics of a marriage to list, so I just name the database, where it is located and the date I checked it.

Results/Comments: NIL, found other Dillard marriages 1833-1835 in Oglethorpe, Jefferson, Bibb, Stewart, Telfair counties; not all Georgia counties are included in this database and not all of the counties that are listed have marriage records for the correct time frame.

When you don’t find anything, you can use NIL which is short for “not in location.” I like to add comments that help me understand why it might not have been there. If I did locate the record, I would detail all of the information in this column. It tells me at a glance exactly what I found. Using the copy and paste function makes it easy.

That’s all there is to it. As I work down my research plan I add each search. In the midst of my research if I discover another website to search for the marriage record I enter it into my research log as well. It holds every site that I’ve searched. It takes some discipline to start using a research log, but once you start you’ll love the feeling of accomplishment. An hour of research where you didn’t find anything doesn’t feel wasted. Instead you have all of your searches entered and you’ve discovered that you need to rethink your hypothesis.

In the case of Cynthia Dillard and her marriage. I’ve discovered a possible father, George W. Dillard. The county in Georgia where he was living in the 1830’s had a courthouse fire and destroyed the marriage records for that era. It just might be that’s the reason I can’t locate a marriage for Cynthia and Thomas Royston!

Research Ties

The third type of research log that I use is Research Ties. This is an online research log that I use when recording multiple results from the same source. This is especially helpful when extracting all the entries of the surname you’re researching from a microfilm. You may not know how everyone is related, but while you’re looking at that film you might as well get all of the surname entries to save time in the future.

With Research Ties I can enter in the source information once, then add each result as I find it with specific details. In the screenshot below, I’ve used the program to log all the entries of Royston’s found in the Chambers County Deed book index. You’ll notice the source information is repeated and all I had to add was the specifics. This particular index had entries for about 20 Royston individuals. Research Ties made the task of recording each entry fast and easy.

I can export all the information that I’ve added either as a PDF or spreadsheet. Entries for the individual I’m specifically researching could then be copied and pasted into my Google sheet research log. When I begin researching another individual, the information is there waiting for me.

Research Ties has a nice feature that allows you to upload images of the sources you locate and the URL’s so that you can easily view them straight from the program. It syncs with FamilySearch so you can quickly create a new source for your ancestor using the information that you’ve already entered.

With a free trial available you can try it out and see how it might help you. Make sure you start with the Learning Center and go through all of the tutorials to get a feel for the program. The Research Ties team is always looking for ways to make the user experience better.

Assignment

Your assignment? Start following your research plan and log your results using a research notebook, an electronic research log, or Research Ties. Be sure to create source citations for what you’ve found.

Best of luck in all of your family history endeavors. Go to the next step: Research Like a Pro, Part 6: Write it Up

9 Comments

Leave your reply.