In this series we’ve discussed the important resources to consult for your Irish ancestor in America. At this point, you should hopefully be armed with some specifics about your ancestor, their Irish-born family, and an idea of what province, county, or parish they came from in Ireland. Now, we will cross the Atlantic and examine the resources you will use in Ireland to pinpoint your ancestral family.

First, it’s crucial to provide some historical context for Ireland and its records. As far back as the 18th century, most of the Irish population outside of Ulster were tenant farmers who rented their land from larger estates. By 1870, 97% of the land was rented out, and half of Ireland belonged to just 750 families. Therefore, beyond church records you’ll likely see distressingly few documents for your Irish ancestor, especially if they lived on rural land before the 1850s. Another obstacle is the loss of the Ireland Census. While researching American records, you’ve likely appreciated the intrinsic value of censuses to genealogy. Although Ireland kept censuses regularly from 1821 to 1911, the 1821-1891 censuses were destroyed either by bureaucracy or by the fire at the Public Record Office in Dublin in 1922. Another important event for Ireland (and its records) was the Partition of Ireland in 1921, when the island divided into Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Before 1921, however, Ireland was one nation and most country-wide genealogical records can be found through websites and institutions from the Republic of Ireland. If you’re researching a Northern Irish family post-1921, or if you’re looking into specific parishes in Northern Ireland, you should direct your searches to websites like nidirect.

Now that we know a little about the history of Ireland—and its obstacles for family history research—let’s examine what Irish records we have to work with. While there are smaller-scale resources in any given Irish county or parish, here are the major resources that will be most informative for your ancestor.

Censuses—What Survives

The majority of censuses had been destroyed, but some escaped unscathed. The 1901 and 1911 Ireland Census are the only surviving, public censuses that cover the entirety of the island. Digital images of the censuses are free through the National Archives of Ireland. The kind of information they provide include a resident’s address, age, religion, literacy, occupation, birthplace, and if they spoke the Irish language. If your ancestor lived in Ireland in the early 20th century, these censuses can be a valuable insight into their household and family.

Fragments of the 1821-1851 censuses also survive, but they only cover parts of certain Irish counties. Still, they are worth examining here in case a census covering your ancestor’s county survived. There are also the 1841 & 1851 Ireland Census Search Forms, which provided shorthand information from censuses for people applying for Old Age Pensions. These can be searched on FamilySearch.

Vital Records

The General Register Office of Ireland (GRO) began civilly recording births, marriages, and deaths in 1864. The GRO also recorded non-Catholic marriages as early as 1845. Birth and marriage records can provide your ancestor’s full name, residence, names of parents and their occupations. Death records are less informative (they typically don’t provide parent-names), but still offer age, occupation, and former residence. And good news, digital images of Irish vital records are available for free at irishgenealogy.ie! Keep in mind that vital records post-1921 were recorded separately in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. If your ancestor lived in Northern Ireland, vital records can be accessed here.

Church Records

Church records will likely be the main source for your research, since they are the largest collection of Irish records and cover centuries of life events. As discussed in previous posts, the two major religious denominations in Ireland were the Catholic Church and the Church of Ireland (i.e. Protestant). If you know your ancestor’s denomination but not the parish they came from, you can try country-wide or county-wide searches using RootsIreland or IrishGenealogy.ie, which cover both Catholic and Protestant records.

While some Catholic parishes began keeping records in the 1700s, most parishes—especially in rural areas—did not formally keep records until after the 1820s. The years covered by surviving Catholic church records varied widely from parish to parish; check out this Irish Catholic parish map to see what years a given parish covers. Catholic records in 19th century Ireland typically didn’t provide much information for an ancestor (details like residence, age, and occupation were often excluded), but they’re still essential in that they’re often the only reliable resource for tracing Irish Catholic ancestry. Digital images for many Catholic parishes are available on the National Library of Ireland website. They can also be searched on Ancestry.

Protestant records started much sooner, with the Church of Ireland consistently keeping records as early as 1770-1800. However, the range of surviving records vary from parish to parish. A table of surviving records exist on The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers. The amount of information in the parish registers depends on the decade they were created, but like Catholic parish records they are essential to documenting early Irish Protestant ancestors. The most comprehensive site to search Protestant records is RootsIreland.

Taxes, Tithes, and Estate

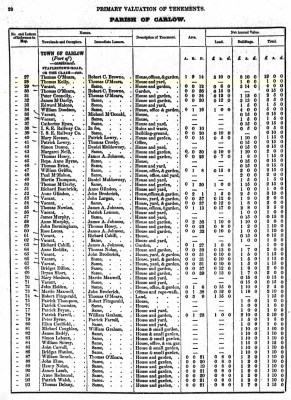

Aside from vital records and church records, you can find a useful resource taxes, tithes, and estate papers. The largest and most comprehensive resource is the Griffith’s Primary Valuation. This was a country-wide survey completed 1848-1864 for the purpose of valuating properties for taxes. It documented the size and value of a piece of land, as well as who occupied it. Griffith’s didn’t list out families, but rather the tenant directly renting the land and the owner leasing it. Still, this is a good resource for confirming where your ancestor lived, and is the closest substitute to a mid-19th century census. Griffith’s can be searched for free on Ask about Ireland, or you can access original images on Ancestry.

Aside from vital records and church records, you can find a useful resource taxes, tithes, and estate papers. The largest and most comprehensive resource is the Griffith’s Primary Valuation. This was a country-wide survey completed 1848-1864 for the purpose of valuating properties for taxes. It documented the size and value of a piece of land, as well as who occupied it. Griffith’s didn’t list out families, but rather the tenant directly renting the land and the owner leasing it. Still, this is a good resource for confirming where your ancestor lived, and is the closest substitute to a mid-19th century census. Griffith’s can be searched for free on Ask about Ireland, or you can access original images on Ancestry.

Another important resource is the Tithe Applotment Books. Compiled by the Church of Ireland in 1823-1837, it lists occupiers of land who would be eligible to pay tithes (regardless if they were Protestant or Catholic). Like Griffith’s, only heads of households were named rather than family members. Urban areas (like Belfast and Dublin) were excluded from the Tithe. Again, this is an excellent substitute for the early Irish censuses that had been lost. You can search the Tithes on the National Archives of Ireland website.

As discussed above, much of Ireland was owned for centuries by large estates. If you know from Griffith’s or the Tithe where your ancestor rented land, the papers of the estate-owner may offer more details on your ancestor’s family. Few estate papers are available outside of Ireland, however. Check out the holdings at the National Archives of Ireland for more information.

It should be noted that Irish tax records contributed to an important search tool for Irish research. This surname tool, based on Griffith’s Primary Valuation, can cross-reference two Irish surnames and show which parts of Ireland they appear together. If you don’t know where your Irish ancestor originated but you know the surnames of their parents, this tool can help you narrow down possible places where they came from.

Newspapers & Court Records

While Irish newspapers are not consistently reliable for genealogy, they’re still worth checking for your ancestor. Marriages, obituaries, and funeral notices were not commonly published in Ireland like they are in America, but your ancestor may be referenced in events that took place in their hometown. Many Irish newspapers are available online on FindMyPast.ie.

Do you think your ancestor committed a crime? They could be mentioned in Ireland’s Petty Sessions Court Registers. This collection covers most counties in Ireland from 1828 to 1912. They name the plaintiffs, defendants, crime, and sentence. While not incredibly informative, they can add flavor and context to your ancestor’s life. The Registers can be searched on FindMyPast.

Words of Caution

Now that we’ve discussed the main resources available in Ireland, it’s important to provide some words of caution for your research. First off, your ancestor’s first name and/or surname may be different in Ireland than it is in America. There are many variations of Irish first names that can appear nonsensical; for example, Delia is a common nickname for Bridget, and Darby is a variation of Jeremiah. Check out a comprehensive list of first-name variations here. Surnames can have even greater disparities. Sometimes Irish surnames are a product of Gaelic translating into English, while other times they’d been spelled out phonetically so many times before they finally stick with one spelling. I once researched an Ayers family in America, found out that they had immigrated using the surname Ehers, and finally found them in Ireland under the surname Ears. Do some digging on the history and origins of your ancestor’s surname, and look at lists of surnames that show up in Irish records for comparison. Above all else, proceed with caution when searching for your ancestor’s name and keep an open mind.

Another word of caution relates to Irish birth dates. Many Irish immigrants were illiterate and therefore didn’t know when they were born, or only had a vague approximation. Many would attribute their birth as having occurred in March, but this month is special to the Irish thanks to Saint Patrick’s Day, so take professed March birthdays with a grain of salt. If you do have a pretty solid birth date for your ancestor, the last hurdle is Irish civil birth records (if your ancestor was born post-1864). The General Register Office was originally a British institution, so registering a child’s birth meant reporting it to the British government. Naturally, many Irish—especially Catholics—weren’t keen on this idea. The government then imposed a fine if a child wasn’t registered within three months of their birth. Rather than register the child’s birth on time, parents often waited as long as six months to register their child and then gave a false birth date to avoid paying the fine. I even found one set of parents delaying a full year before having an aunt register the baby’s birth in the next county over to avoid suspicion. In the case of Irish Catholics, a baby’s baptism date is often closer to their actual birth date (i.e. within several days) than the date on their civil birth certificate. Indeed, don’t be surprised if your ancestor had been “miraculously” baptized a few months before they were reportedly born. If you find additional inconsistencies between your ancestor’s church records and civil records, just remember that Irish Catholics were more likely to answer to the Church than to the government.

I hope this overview of important Irish records and resources gives you direction on where to carry on your search for your ancestor. While there are many challenges and roadblocks, there are also many avenues you can take to find your family’s Irish origins. Because of the inherent challenges in Irish research, it’s that much sweeter when you find the answers you’re looking for and can pinpoint the town of your ancestor’s birth.

Next, we’ll look at how to find the modern locations of townlands, parishes, and farmlands found during your hunt for your Irish ancestor. Until then, Happy New Year!

Irish Research Series

Tracing your Irish Ancestors Part 1: Ask the Right Questions

Tracing Your Irish Ancestors Part 2: American Resources

Tracing Your Irish Ancestors Part 3: Family, Community, and DNA

Tracing Your Irish Ancestors Part 4: Records in Ireland

Tracing Your Irish Ancestors Part 5: Irish Jurisdictions and Finding Your Ancestral Home

Tracing Your Irish Ancestors Part 6: The Power of Local History

2 Comments

Leave your reply.