Claude 4.5 Sonnet assisted with organizing and writing this blog post based on my research report and a syllabus about using AI for court records.

For generations, genealogists have known that court records contain some of the richest genealogical information available—and some of the most challenging to access. Unlike vital records or census enumerations, court records rarely come with indexes. The researcher faces the daunting task of browsing court books page by page, deciphering cryptic clerk notes, understanding archaic legal terminology, and piecing together fragmented narratives that can span multiple documents over several years.

But what if you could search every word in thousands of handwritten court pages in seconds? What if you could ask an AI assistant to explain 18th-century legal terms or organize a complex multi-year litigation into a coherent timeline? These capabilities aren’t hypothetical—they’re available now and revolutionizing how we work with court records.

Let me show you how this works in practice through a real research example: the quest to identify Samuel Daniel of Middlesex County, Virginia, who advertised for his runaway apprentice in 1770.

Chat GPT Image

I wrote previously about John Royston, the runaway apprentice in Disappearing Act: John Royston Apprentice (1750 – after 1814). I had not previously researched Samuel Daniel of Middlesex County, Virginia, who had apprenticed John, and set an objective to do so.

Research Samuel Daniel of Virginia, who advertised for his runaway apprentice, John Royston, in the Virginia Gazette in 1770. Samuel Daniel was likely born before 1740 in Virginia. John Royston was born in 1750 in Gloucester County, Virginia, and died after 1816 in Georgia.

The Samuel Daniel Challenge

The starting point was simple: a February 1770 newspaper advertisement in the Virginia Gazette where Samuel Daniel sought his runaway apprentice, John Royston.1 Beyond this ad, nothing was known about Daniel. Was this the right county? What was his occupation? What happened to him? The answers lay buried somewhere in Middlesex County’s court records—but where?

Traditional research would have meant systematically reviewing court records page by page, hoping to spot Daniel’s name among hundreds of other cases. The breakthrough came from a different approach entirely.

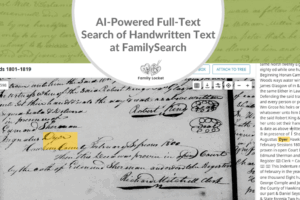

Discovery Through AI-Powered Full-Text Search

FamilySearch’s Full-Text Search tool, powered by AI, reads handwritten documents and makes every word searchable. Instead of manually scanning digitized images, I searched for “Samuel Daniel” across the relevant Middlesex County court records. In the FamilySearch Catalog, I navigated to the page for Middlesex County, Virginia, then selected “Court records.” That catalog shows 29 records, but I narrowed it by date. I wanted the original court order books and found a great collection, all digitized and available for full-text search.

In the image below, I’ve highlighted the two collections I was most interested in, given that John Royston’s disappearance occurred in 1770. I wanted to search both before and after the date. By clicking on the notebook icon on the far right with the AI symbol, you can go directly to that collection and use full-text search only within those records. This is very beneficial in narrowing the search. You can also note the Image Group Number (IGN) and use it in the main full-text search window to narrow the results.

FamilySearch Catalog: Middlesex County, Virginia, Court Records

The AI technology identified every page where “Samuel Daniel” appeared, highlighting the relevant passages.

The results were remarkable: twelve separate court record entries spanning April 1773 through March 1774, documenting a complex legal dispute between Samuel Daniel, John Royston, and Richard Wiatt Royston. These records would have been more time-consuming to find through traditional browsing—they appeared scattered across multiple court sessions over two years. These order books do have an internal index, but full-text search was much more efficient – especially since I could search by “Samuel Daniel” and “Royston.”

Search Strategy Tips

Based on this successful search, here are key strategies for using Full-Text Search with court records:

- Put names in quotes for exact phrase matching: “Samuel Daniel” rather than Samuel Daniel

- Search broadly first, then narrow by date range if you get too many results

- Try variant spellings—AI may interpret handwriting differently than expected

- Search only by surname or first name – ensure that you’re finding all relevant records

- Search specific collections from the FamilySearch Catalog when you know where to look

From Discovery to Understanding: The AI Workflow

Finding the records was just the beginning. The real challenge was making sense of them. Here’s how AI tools transformed this process:

Step 1: Transcription

Each court record entry was transcribed using Google AI Studio. Full-text search provides a transcription that helps when browsing the record, but once I determined it was relevant, I downloaded the record to my digital files and then uploaded it for transcription by Google AI Studio. This provided the AI with the best copy possible and also saved the image to my own files.

The image below shows my very simple prompt. I like to provide the names and always add “preserve the line breaks” so I can easily check for accuracy. You can see that this was not easy script to read – very small and close together.

Google AI Studio Prompt

You can open the AI’s “thoughts” to see the process, which is fascinating. Below is a portion of the AI’s thought process for correctly transcribing the court case.

The Royston-Daniel case was just a portion of the page, but AI was able to extract the section I wanted and correctly transcribe it.

The AI transcription preserved the original structure while making it readable. My next step was to check accuracy against the original image, and I found it was very accurate.

Step 2: Logging the Research and Compilation

Using my Airtable research log, I entered each court order – twelve in all. I arranged them chronologically and, to keep them straight, wrote the dates as “1773- April,” etc. After AI transcribed the record, I added that to the research log as well. Since the records were all from the same image group on FamilySearch, I could duplicate the source citation and then adjust the page number, image number, names, date, and URL.

Once I’d logged all twelve court entries, I compiled them into a single document with:

- A title for each entry (e.g., “April 1773 Court Order – Royston v. Daniel”)

- The full transcription

- Source citations with FamilySearch links

- Document dates and page numbers

This compiled document became the foundation for deeper analysis.

Step 3: AI-Assisted Organization

My next step was to upload the compiled court record document to Claude AI with a specific request: create a chronological table showing the date, parties involved, action, and outcome for each entry.

The result was a comprehensive table that showed at a glance the basics of the cases.

| Date | People Involved | Action | Outcome/Notes |

| April 1773 | Richard Wiatt Royston (Plt.) vs. Samuel Daniel (Def.) | Trespass upon the Case | Imparlance granted |

| May 1773 | Samuel Daniel (Plt.) vs. Richard Wiatt Royston & John Royston (Def.) | Covenant | Richard returned as “no inhabitant”; suit abated |

| June 1773 | Richard Wiatt Royston (Plt.) vs. Samuel Daniel (Def.) | Trespass upon the Case | Verdict: Defendant guilty; £5 1s 2d damages |

| March 1774 | Samuel Daniel (Plt.) vs. Richard Wiatt Royston (Def.) | Covenant Broken | Verdict: £10 plus costs awarded to plaintiff |

What appeared as a confusing jumble of legal proceedings began to make sense. It seemed to be the aftermath of the broken apprenticeship agreement, with both parties suing each other and the case evolving over time.

Critical Considerations

While AI dramatically accelerates court records research, maintain professional standards:

Verify Everything

- Always check AI transcriptions against original images

- Cross-reference AI explanations of legal terms with historical legal dictionaries

- Confirm relationships and conclusions through traditional genealogical methods

Document Your Process

- Record which AI tools you used and when

- Save important AI conversations as part of your research documentation

- Include AI assistance in your methodology notes

Understand Limitations

- AI can miss records, so manual review remains important as backup

- AI may make incorrect assumptions about relationships

- The burden of proof still lies with the researcher

Cite Appropriately

- Credit AI assistance in your research notes

- For example: “Claude AI helped organize and analyze court proceedings, 31 January 2026”

- Link to saved conversations when possible

Best Practices: The RGTF Framework

When working with AI on court records, use this framework:

R – Role: “You are an expert genealogist specializing in 18th-century Virginia court records.”

G – Goal: “I need to understand the legal proceedings between Samuel Daniel and the Royston family.”

T – Text: Upload your compiled court records document or paste the transcriptions.

T – Task: “Create a chronological table showing dates, parties, actions, and outcomes. Then explain the legal terminology and analyze what these proceedings reveal about their relationship.”

F – Format: “Present findings in a table followed by narrative analysis. Include citations to specific court entries.”

Looking Forward

Court records have always been treasure troves of genealogical information—they just required tremendous effort to access and interpret. AI hasn’t changed the value of these records, but it has dramatically reduced the barriers to using them effectively.

As FamilySearch continues adding collections to Full-Text Search and AI tools become more sophisticated, we’ll see even greater possibilities:

The Samuel Daniel research, completed in just two weeks as part of a 14-day challenge, demonstrates what’s possible today. What took previous generations months or years of courthouse visits can now be accomplished from home in days—without sacrificing scholarly rigor.

The key is approaching AI as a powerful assistant, not a replacement for traditional genealogical methods. Use it to find records faster, understand them more deeply, and organize them more effectively. But always verify, always document, and always apply the fundamental principles of sound genealogical research.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll review the court records and see how AI helped analyze and make sense of the case.

Best of luck in all your genealogical research!

Sources

- “Middlesex, February 9, 1770,” John Royston, run away from the subscriber, The Virginia Gazette (Rind), No. 021, Thursday, 9 March 1770, p. 4. col. 2, para.; imaged, Colonial Williamsburg (https://teacherresources.colonialwilliamsburg.org/API/Download/v1_0/GetOriginalLimited?Identifier=CW11851S&SourceAction=API_VIEW_DETAILS_TRX&UsePreviewPdf=False : accessed 27 September 2025).

Leave a Reply

Thanks for the note!