What is the best advice for those beginning to research their ancestor from German-speaking lands? Seek out their church records in America to discover their German hometown and parents. German research expert Roger Minert estimates that church records will be the best source of this information 65-76% of the time. Dr. Minert is the editor of a 35 volume (so far) series of books cataloging those German-Americans who have a hometown listed in their church records. (1)

Like researching any immigrant, we will start by making an exhaustive search of what we know here in America before we try to move back to the country of their birth, which includes looking for the U.S. census, city directories, newspapers, ship passenger lists, military records, and more. Yet, for most 19th century Germans, focusing on finding German church records will be the key to finding their birth information and parentage.

While we want to research everything we can find about our German’s American experience, the key questions, to begin with, will be:

What was their religion?

Where did they go to church?

Katholisch or Evangelische?

As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, most Germans from the smaller Protestant sects immigrated in the 18th century. The political climate in the 17th and 18th centuries made it likely that most of those smaller sects no longer existed in Germany by the 19th century because most of their members had immigrated or converted to a state religion. The image below depicts religion in the 1895 German Empire: Tan Color=Protestant, Aqua=Catholic, Pink=Mixed

Meyers Konversationslexikon, 5th edition, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Verbreitung_der_Konfessionen_im_deutschen_Reich.jpg : accessed 24 Apr 2021).

Because of this earlier migration of the smaller Protestant sects, most 19th century German immigrants were members of one of three state religions: Roman Catholic (Katholisch), Lutheran (Evangelische), and lesser so Reformed or Calvinist (Reformierte Kirchen). Hence the vast majority of 19th century Germans were either Catholic or Lutheran. Because immigrants rarely changed their religion when they came to the U.S., it is vital to discover their religion so you can find any church records created in America. Likewise, it will be nearly impossible to research your ancestor in Germany without knowing their religion.

One advantage of German ancestors is that both in Germany and in the U.S., German church records are frequently detailed and accurate and will often list parents, their hometown, or both. According to Roger Minert, Protestant church records will be the most likely to name the immigrant’s hometown, while American Catholic records will tend not to. This has been my experience, but Catholic records also have a good chance of listing parents. Moreover, the birthdates found in German immigrant American records are often accurate, which is advantageous when trying to find your ancestor in Germany.

To illustrate German-American research, we will follow German immigrants, Christine Röckemann (1838-1919), and her husband, Burkhard Schlag (1830-1876), in their journey to St. Louis.

Christine Röckemann-Schlag seated on the right, with her daughter and great-granddaughter circa 1910, St. Louis, Missouri. (2)

Research in American records

The research process is the same for everyone. Start from what can be known about your ancestor, and work backward in time. Create a timeline with the records you find for your German and their FAN club (i.e., friends, associates, and neighbors). Make a locality guide for the American town they immigrated to. Uncover everything you can because you won’t know what record may contain your ancestor’s hometown or parents. However, focusing on their church records will most often be the key. Start by asking what their religion was and where they went to church.

Research their pastor: civil marriage records

Though civil marriage records may have less information than a church record, they are important to check because most of the time, the minister who performed the ceremony will be listed. Researching the pastor can unlock what church they attended and reveal your ancestor’s religion.

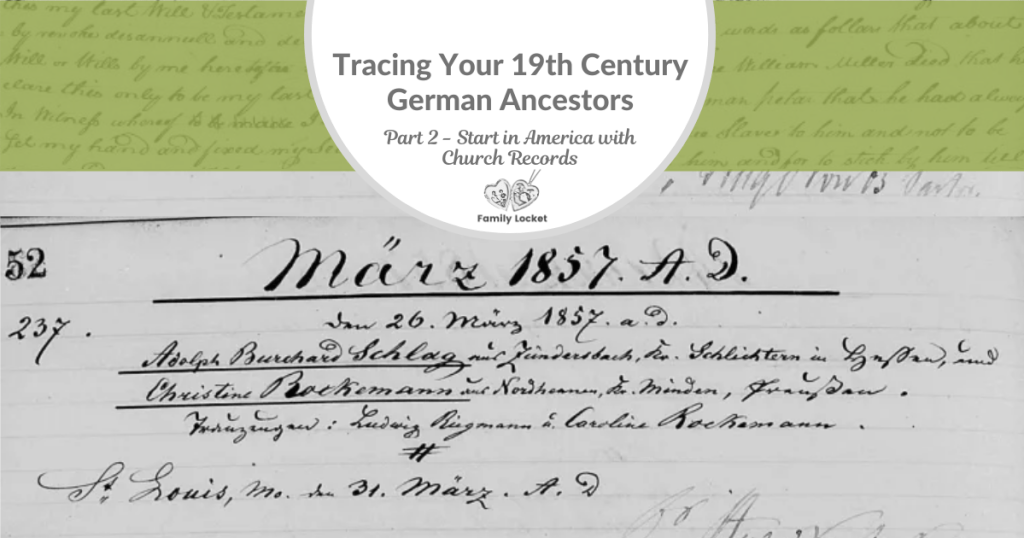

Even when blown up, the 1857 civil marriage record shown below is hard to read, but the pastor’s name, Dr. Hugo Krebs (underlined in red), is legible. Researching the pastor, Hugo Krebs, led to finding the Lutheran church Burkhard and Christine attended and then discovering their church records, as well as those for their family and friends.

Researching their church in a larger city: city directories and newspapers

Along with census records, be sure to trace your German through city directories that can be found for larger cities (in Ancestry, FamilySearch, Fold3, or Google books), but also use these directories to understand the churches and their pastors of that time and place. Newspapers are also a great source; however, your ancestor or their pastor may not have made the papers as much in a larger city.

If you cannot find their pastor and church via a civil record, newspaper, or another record, you may be able to use the city directory to map out where your ancestor lived and what churches were nearby. Perhaps you know what religion your German’s descendants were, so you can look in the directory for the names and locations of churches of that religion in the immigrant’s neighborhood. In the case of Burkhard and Christine, the St. Louis County Library has a dedicated webpage to historic German churches in the city.

Looking up churches in a city directory can help you discover what churches were in your German’s neighborhood, and may also list the pastor found in your German’s civil record. This directory revealed Hugo Krebs as the pastor of the Holy Ghost Lutheran Church. This information was used to find the church marriage record of Christine and Burkhard shown above.

Churches and pastors in a rural area

If your ancestor settled in a rural place, it might be harder to identify churches and their pastors with a city directory, as they were not usually created for rural localities. However, on the positive side, there were probably only one or two churches in the area that your ancestor would have attended. Also, newspapers in rural areas often have a wealth of details in the life events of your specific ancestor. It can be easier to find your ancestor and their pastor to discover their religion and church with fewer people in the area.

German-language newspapers

Often much more specific information about our ancestors can be found in German language records, including newspapers. Using German Newspapers When You Don’t Know Much German is a great webinar for searching German-American newspapers. The font found in older German typed documents is called Fraktur. Download a Fraktur font if you don’t already have one. Here’s the one I downloaded: Breitkopf Fraktur. There is also one on Google Docs called UnifrakturMaguntia. To translate a German newspaper, you can type out what you see in Fraktur, change the font to something easier to recognize, and then use Google Translate to read it in English.

Other American records to look for

Ship’s passenger lists may show an immigrant’s German state and occupation, but rarely their hometown. Nevertheless, it is important to look for the passenger list of your German, especially to see fellow passengers. Look for their passenger list in the ports they may have left from and where they arrived. Mid-19th century Germans were often leaving from Hamburg, Bremen, or Le Havre, and sometimes passed through an English port like Southampton or even Liverpool. The Hamburg Passenger List (1850-1934) can be among the most helpful to check for a German’s hometown (sadly, much of Bremen’s & Le Havre‘s were lost).

Germans arrived through all the familiar east coast ports, such as New York and Philadelphia, but in the steamship age, some increasingly went through the port of New Orleans. 19th-century German immigration was stoked in part by overpopulation, as inheriting enough land to farm in their homeland became harder and harder. Many immigrated because of the opportunity to own land. As the west of North American began to be settled, many Germans came through the port of New Orleans and up the Mississippi, Missouri, or Ohio Rivers to settle in the cities along this river system (e.g., St. Louis, Cincinnati, Chicago, Minneapolis) or to get to farmland in the Midwest.

Christine (highlighted in red in the image below) arrived on 27 Apr 1854 with her sister Caroline (entry above Christine) and many others from a place called Friedewalde (highlighted in yellow). Friedewalde is a small locality near the bigger town of Minden, in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. In fact, looking at the whole passenger list revealed most of the over 200 passengers were from various localities near Minden. Christine clearly had a huge FAN club!

Passenger List (5)

Who did they immigrate with?

Usually, the most important reason to try to find your German on a passenger list is gathering clues about who they traveled with. In contrast to other groups such as the Irish, impoverished Germans mostly did not emigrate. The Germans that immigrated to the U.S. tended to have enough money, usually from selling everything they had, to bring their whole family. Sometimes several families immigrated together from the same village. The research process includes understanding the FAN (friends, associates, neighbors) club of our ancestors, which can be particularly important to Germans. If you cannot find your German’s hometown, perhaps you can find the hometown of someone they immigrated with.

Naturalization records are important to check; however, the later your German immigrated, the more helpful these records are likely to be. If they can be found for mid-19th century immigrants, naturalization records will likely be shorter and may give the state your German was from. In this era, women often were not naturalized as individuals but had their husband’s naturalization status.

In the example of Christine and Burkhard, Christine did not have a naturalization record, and Burkhard’s added no new information. His 1860 naturalization was found, but the only information on it was that Burkhard renounced the Prince of Hesse, and his German state had already been seen on census records. This was common on earlier naturalizations, but some do give more information, so it’s important to check.

Did your German go back home to visit? In the age of the steamship, it was much easier to do. Burkhard went back to his homeland in the fall of 1866 as an American citizen. This gives a hint that his visit may have generated records of his visit in Germany in addition to the U.S. passport application shown below.

Passport Application for Burghard Schlag (6)

Find your German’s church marriage record

All the American research led to finding Burkhard and Christine’s religion and church: Holy Ghost Lutheran Church (English name). The next step was researching whether this church had existing records. In this case, the English name of their church was used to find their church’s records online in FamilySearch. Their civil marriage record gave the date they were married, so once the unindexed online record set was found for their church, then the church book could be electronically flipped through to the correct date. If you cannot find your ancestor’s church records online, try next to contact the church (or its modern governing body) or a local genealogical society for help.

In Christine and Burkhard’s German-American Lutheran church, Evangelische Heilige Geist Kirche, the following marriage record was found (Figure 7). It did not list their parents, but it did list each of their hometowns very specifically with three jurisdictions: village, kreis (like a county), state. Many more records for Burkhard and Christine’s family and their friends were found at this church. Finding these records was worth the effort of asking the right questions!

Who was their pastor?

What was their religion?

What church did they go to?

Do their church records still exist?

How can they be accessed?

Church Marriage Record: Translated it reads 26 March 1857 AD, Adolph Burkhard Schlag, Zündersbach (sp), kreis Schlichtern (sp), Hessen and Christine Rockemann, Nordhemern (sp), kreis Minden, Prussia. Witnesses: Ludwig Riegmann & Caroline Rockemann (Christine’s sister). St. Louis, Mo. on 31 March 1857, Dr. Hugo Krebs, Pastor. (7)

Now that we know their hometowns, we will pick up the search for Christine and Burkhard’s families later in this blog series. In Part 3, we will begin to listen like a German to be sure we know what their name sounded like to others to find their records and discover their true name in German.

For a helpful webinar see: Finding Your Ancestors’ German Hometown ($).

Good luck as you continue your search for your German ancestor!

Other parts of this series:

Part 1: Tracing Your 19th Century German Ancestors- Which Germans?

Part 3: Tracing Your 19th Century German Ancestors: Tips for Getting the Surname Right

Part 4: Tracing Your 19th Century German Ancestors: Comprehend Enough German

Part 5: Tracing Your 19th Century German Ancestors – German Archives

Part 6: Tracing Your 19th Century German Ancestors: Using DNA

(1) Minert, Roger P.(editor), German immigrants in American church records -35 volumes so far. (Rockport, Maine : Picton Press, c2005-2015 and Orting, Washington : Family Roots Pub. Co., c2016-). Here is a link to Roger Minert’s website on this series: https://rpmgrtpublications.wixsite.com/mysite. Here is a link to this series at Family Search.

(2) Ancestry, (https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/20924143/person/1009433124/media/6591f702-1c00-4207-9577-2099c79de2a9?: accessed 24 Apr 2021) > Search > Public Member Trees > Christina Reckermann > Boshoven Family Tree > uploaded 4 Oct 2010.

(3) Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1171/images/vrmmo1833_c6134-0199?: accessed 24 Apr 2021) > Missouri, U.S., Marriage Records, 1805-2002 > St Louis > Record images for St Louis > 1853-1860 > image 201 of 596 >“Burchard” Schlag and Christine “Bockermann” (purple).

(4) Ancestry, (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/11437522?: accessed 24 Apr 2021) > U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 > Missouri > St Louis > 1864 > St Louis, Missouri, City Directory, 1864 > image 43 of 487 > Church of the Holy Ghost.

(5) Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7484/images/LAM259_39-1129?: accessed 24 Apr 2021) > New Orleans, Passenger Lists, 1813-1963 > M259-NewOrleans, 1820-1902 > 39 > image 759 of 770 > “Christine Bockemann.”

(6) Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1174/images/USM1372_142-0985?: accessed 24 Apr 2021) > U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925 > Passport Applications, 1795-1905 > 1861-1867 > Roll 142-01 Aug 1866-30 Sep 1866 > image 931 of 1325 > “Burghart Schlag.”

(7) FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS77-C4QV : accessed 24 Apr 2021) > Church and school records, 1834-1961, Holy Ghost Church (St. Louis, Missouri) > Marriages, v.1-5, p.1-279 Jan1834- Oct 1882, image 567 of 973.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.